Conglomerate is a very unique looking and highly variable rock. It doesn’t get enough credit for how beautiful it can be, and many people aren’t even familiar enough with it to be able to readily identify it.

It is easy to confuse conglomerate for other rock types, or even to dismiss it as a rock altogether. But conglomerate is a well-defined and fairly widespread rock type that can be found all over the world, so it’s worth knowing what it is and how it is identified.

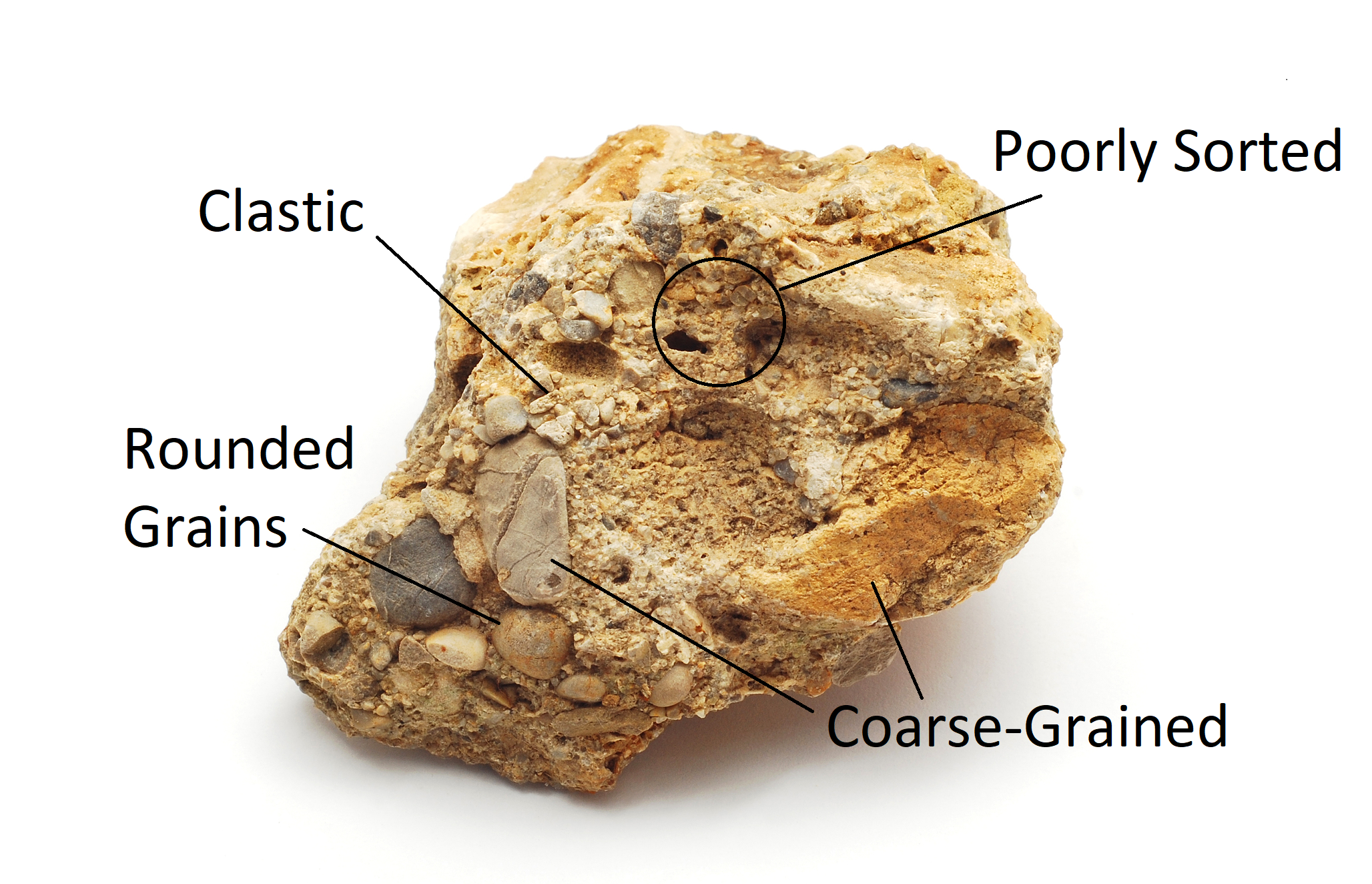

Conglomerate is a clastic sedimentary rock made from many different sizes of rounded grains, many of which are gravel-sized or larger. These grains are fragments of other rocks, bound together by cement which is typically silica or calcite. The grains are well-rounded, which differentiates it from breccia.

While conglomerate is a clearly defined rock type, there are many different varieties and it can easily be confused for similar, closely related rocks. I’ll walk you through how to identify conglomerate, what different varieties look like, and where it can be found.

What Does Conglomerate Look Like?

Conglomerate is made up of bits and pieces of other rocks and minerals, which means that its appearance is, in large part, determined by what those original rocks looked like. Because every conglomerate’s source rocks are different, there is almost unlimited variety in conglomerate’s appearance.

Despite this variability, all conglomerates have a lot in common that makes them easily identifiable if you know what to look for.

Conglomerate looks like many poorly-sorted rock fragments that have been mixed up and cemented together. The grains range in size from sand to pebbles or even cobbles, often with varying colors due to multiple source rocks. The grains are relatively smooth and rounded, with no sharp points or jagged edges.

Pro Tip: I have created the best rock identification system you’ll find anywhere. It’s made to help everyone from brand new hobbyists to university Geology students, and includes an eBook, digital tools, a video tutorials. Find out more here!

While all conglomerates meet this general description, there is a pretty wide spectrum of conglomerates that can look significantly different from one another. Their differences in appearance are primarily driven by the rock fragments from which they form and their method of deposition.

Color is Driven by Source Rocks

Since conglomerate is made from relatively large pieces of other rocks, it’s only natural that it inherits the colors of those source rocks (parent rocks). In most cases, conglomerates will be made up of pieces of many different parent rocks, giving them a very colorful and disorganized appearance.

For reasons we will get into later, conglomerates tend to be made up of rock and mineral fragments that are fairly hard. Therefore, colors associated with these harder materials are more common in conglomerates.

Quartz and feldspar are some of the common and widespread minerals you’ll find in many types of rocks, and conglomerate is no exception. These minerals are fairly hard and resistant to weathering, so they can travel great distances before reaching their final resting place before lithification (turning into another rock).

Quartz tends to be a milky white or off-white color, while feldspar can be much more variable. Depending on the type of feldspar it may be whiteish, pink, red, or brownish.

While these harder parent rocks are very common, almost any rock can be a parent rock to a conglomerate. This means that any color you see in rocks can also likely be found in a conglomerate, given the right conditions.

Pro Tip: To get a better look at the crystals in your rocks and help with identification I highly recommend picking up a good geologist’s hand lens. I use this one that I got on Amazon.

Some of the coloration in conglomerate comes from its cement. There are three primary cement types: silica, calcite, and iron oxide.

Silica and calcite are general very light in color or even colorless. They are also the most common types of cement. Iron oxide, however, is rust-red and often stains the conglomerate to match.

Texture of Conglomerate

One of the defining features of conglomerate’s appearance is its texture. All conglomerate is clastic and coarse-grained, meaning that it is made up of rock and mineral fragments and that the largest of those fragments are bigger than 2 mm across.

For a sedimentary rock to be considered a conglomerate, a large portion (typically over 30%) of its total volume must consist of large clasts. The rest of the rock is usually made up of sand, silt, or clay-sized particles which help to fill the space between the larger grains and cement the rock together.

The larger clasts must also be rounded or sub-rounded. This means that they don’t have jagged edges or points. They obtain this rounded appearance by being transported over a large distance, and it differentiates conglomerate from Breccia, a closely-related rock type.

How to Identify Conglomerate

Conglomerate is so distinct looking and relatively recognizable that you might think that identifying it is a trivial matter. While that is often the case, that mindset often leads people to misidentify other rock types as conglomerates. As with any rock, it is important to take a more systematic approach when identifying conglomerate.

To identify conglomerate, first look for many different sizes of rock or mineral fragments mixed and cemented together. These fragments may range in size from sand to cobbles and be many different colors. Then, observe the shape of the larger grains to ensure they are rounded or sub-rounded and not angular.

A rock must meet all of these requirements to be considered conglomerate:

- Clastic Sedimentary – Formed from the cementing together of rock and mineral fragments

- Coarse-grained – A significant portion of the rock consists of large (over 2 mm) grains

- Poorly Sorted – Highly variable grain sizes, ranging from sand to pebbles or cobbles

- Rounded Grains – The larger grains are relatively smooth, with no points or sharp edges.

If your rock meets all of those criteria then it is very likely a congolomerate, or at least something very closely related. There are, however, a few closely related rocks (and non-rocks) that people sometimes confuse for conglomerate.

Tip: This article is part of my sedimentary rock identification series. To read more about how to identify all igneous rocks, check out my article here.

Breccia is conglomerate’s closest relative in the rock world. It is essentially the exact same thing as conglomerate, but with angular or sub-angular grains instead of rounded ones. This just means that the large rock fragments have edges and points, indicating that they haven’t been transported very far before deposition.

Metaconglomerate is a metamorphic rock type that forms when conglomerate undergoes low-grade metamorphism. The low temperatures and pressures it is subjected to aren’t enough to fully transform the rock as you see in many other metamorphic rocks, but it is enough to change how the rock behaves structurally.

The easiest way to tell the difference between conglomerate and metaconglomerate is how the rock breaks. If it breaks cleanly through the larger rock fragments then it is metaconglomerate, but if it breaks around them then it is just regular conglomerate.

Another issue I encounter fairly frequently is people confusing concrete for conglomerate. This is understandable, since concrete is essentially a manmade conglomerate – a mixture of aggregate (rock fragments) and cement. However, by definition, rocks are non-manmade.

You can usually tell the difference between concrete and conglomerate by looking at the distribution of rock fragments and the color of the cement. If there is a noticeable lack of intermediately sized grains and the cement is the characteristic gray color, you almost certainly have a piece of cement.

What Is Conglomerate Made Of?

It is difficult to define what conglomerate is made from because it can literally be comprised of fragments of a virtually unlimited selection of one or more parent rocks. This means that conglomerate isn’t defined by mineralogy, but rather by its depositional setting, grain size, grain sorting, and grain shape.

However, that doesn’t mean that we can’t make some broad generalizations about what conglomerate is made from. As a clastic sedimentary rock, conglomerate is, by definition, composed of rock and/or mineral fragments. These fragments are broken pieces of older rocks that have been eroded, weathered, and transported to their new place of deposition to form a new rock.

Conglomerate is generally comprised of 30% or more of rock fragments measuring more than 2 mm in size, with sand, silt, and clay making up the remainder of the rock volume. These grains are cemented together by silica, calcite, or iron oxide. The rock fragments can be made of any previously existing rock(s).

It is possible to find fossils in conglomerate, especially if they are still embedded in their original parent rock. For example, a fossiliferous limestone may break apart and be carried down river to be deposited and lithified into a conglomerate with other rock fragments. Any fossils in those pieces of limestone are likely to be preserved in the original structure of the limestone, provided the remaining rock fragments are big enough.

Where Is Conglomerate Found?

Conglomerate is actually a fairly uncommon sedimentary rock. I wouldn’t go so far as to call it rare or exotic, but it isn’t anywhere near as common as its clastic sedimentary brothers shale and sandstone.

You can find conglomerate in several geologic settings including deep and shallow marine environments, glacial deposits, alluvial, and (most commonly) fluvial environments.

In general, congomerates are found in areas with a history of high-energy water flow and rapid deposition which facilitate the transport of large rock fragments without allowing smaller rock fragments time to separate and settle out of the water.

There are some famous examples of particularly attractive and colorful conglomerates, some of which are known as ‘puddingstones’. Some specific examples in the U.S. are the Schunemunk puddingstone formation in New York and New Jersey, and the Roxbury puddingstone near Boston.

I myself recently had the opportunity to visit the Montserrat monastery outside of Barcelona which is famously constructed using pieces the surrounding conglomerate formation. Below is a picture I took of one of the walls outside of the monastery.

How Does Conglomerate Form?

We’ve learned all about what conglomerate looks like, what it is composed of, and generally where it’s found, but I have only briefly touched on how it’s actually formed. The creation of conglomerate is a fascinating process that can vary a bit from setting to setting but always follows a few simple rules.

Conglomerate forms when large, well-weathered rock fragments are deposited by fast-flowing water or a glacier, often as part of a singular debris flow. The large rock fragments are intermingled with smaller grains and later compacted and lithified (cemented) together to form a new, singular rock unit.

It is essential that the large rock fragments have had the opportunity to become weathered and rounded before final deposition. This typically occurs via transportation over a relatively large distance, such as in a river or stream bed. The prolonged and continual movement of the rock along the riverbed causes it to bang against other rocks and chip away at pointy or angular edges, eventually smoothing the surface out.

Over time, these rock fragments become compacted together by the weight of rocks and/or water above them. Then, cement such as silica or calcite precipitates out of the water seeping through the rock fragments to cement them together. The cement slowly grows between the rock fragments until they are fused together, completing the transformation from ‘sediment’ to ‘sedimentary rock’.

What Is Conglomerate Used For?

One of the reasons that you might not be overly familiar with conglomerate (at least before reading this article!) is that it isn’t widely used in practical applications. It is uncommon to see it used in construction or even as decoration.

Conglomerate is used as a filler material or crushed to make aggregate. In rare cases where it is reliably strong it was sometimes used for construction in the past, but is almost never used today. It is also sometimes used for prospecting as an indicator of rocks and minerals that may be found in the area.

One example of conglomerate being used in construction is Montserrat, which I pictured more closely above. This is relatively rare because conglomerate is unpredictable and highly variable, and therefore can’t be relied upon for strength. It is also hard to cut into specific dimensions, making it difficult to build with.

Puddingstone (an unofficial term used for some attractive varieties of conglomerate) is sometimes used for decoration, especially if it is exceptionally colorful. The contrast between its matrix and the larger rock fragments makes it interesting to look at and is very popular with some collectors.

This article is part of my rock identification series. To learn more about identifying rocks, check out my full in-depth guide here.