Coquina is a rock that many people have never even heard of, but it’s one of my favorite rocks because it is so unique and fun to look at. It is particularly interesting because, unlike most rocks, it is almost entirely made up of shell fragments. Because it is so unique, identifying coquina can sometimes be very difficult. I thought it would be helpful to go over how to identify coquina and how it differs from closely related rock types.

Coquina is a clastic sedimentary rock made almost entirely out of large (2 mm or larger) shell fragments. The shell fragments are cemented together by calcite, and it is technically a variety of limestone. Coquina forms almost exclusively in high-energy marine environments like beaches and tidal channels.

While coquina is a clearly defined rock type, it can still be difficult to know whether a rock you’ve found is actually coquina. It can easily be confused for similar, closely related rocks. I’ll walk you through how to identify coquina, what different varieties look like, and where it can be found.

What Does Coquina Look Like?

Coquina is one of the most unique-looking rocks you’ll find anywhere. It gets its name from the Spanish word for ‘shellfish’, and it’s easy to see why.

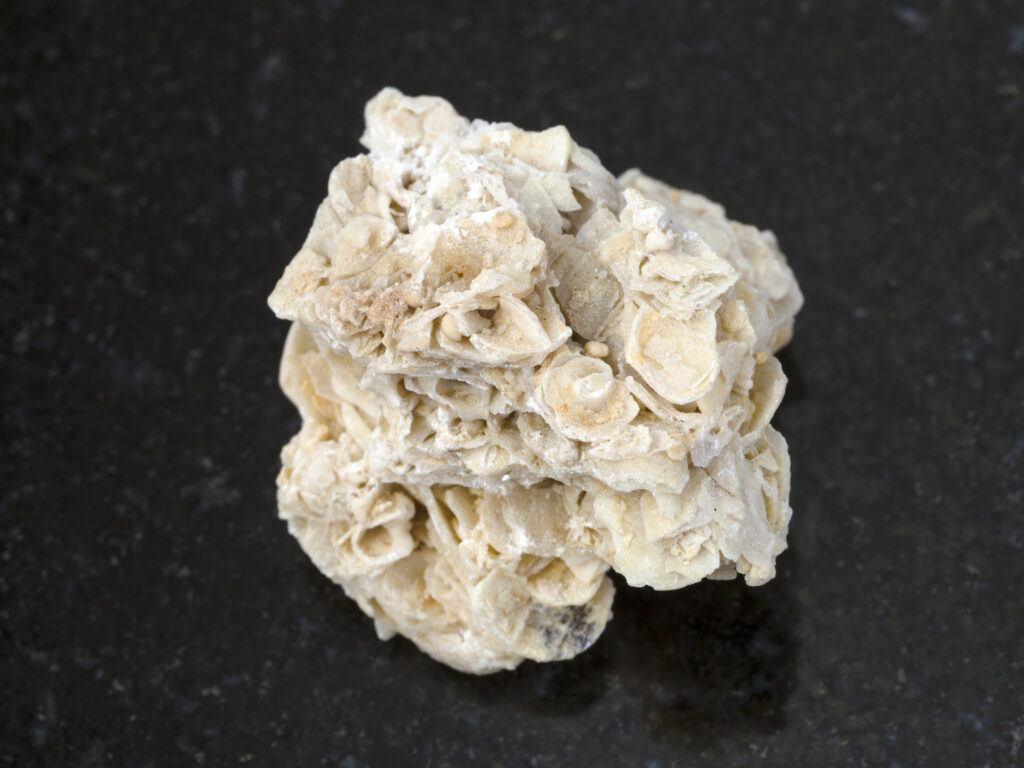

Coquina looks like shells and broken shell fragments fused together. This mass of shell fragments is loosely cemented together, often with a great deal of space (porosity) between them. Coquina inherits its color from the shells from which it is formed and is almost always white, off-white, or light gray.

While all coquina fits this general description, there is still quite a bit of variability from location to location. The size and type of shells, how well sorted the fragments are, and how well cemented they are, all contribute to more variability in coquina’s appearance than you might think.

Pro Tip: I have created the best rock identification system you’ll find anywhere. It’s made to help everyone from brand new hobbyists to university Geology students, and includes an eBook, digital tools, a video tutorials. Find out more here!

Color is Driven by Shell Fragments

Since coquina is made from fragments of shells (or even whole, intact shells), it’s only natural that it inherits the colors of those shells. In most cases, coquina will be made up of pieces of many different types of shells that were all locally present at the time they were deposited.

For reasons we will get into later, coquina tends to have almost no sand, silt, or clay intermixed with the shell fragments. This lack of impurities or contaminants means that the color of coquina is almost entirely determined by the color of the shells from which it formed.

As you likely know, most shells are white or off-white in color. This is because they are made of calcium carbonate, the same mineral from which limestone is formed.

There are, of course, plenty of exceptions. Many shells are streaked with colors like orange, red, pink, or even blue and green. These colors, when mixed together, all contribute to the overall color of coquina. Most of the time this presents as off-white with a tinge of another color, typically light pink or orangeish.

Pro Tip: To get a better look at the crystals in your rocks and help with identification I highly recommend picking up a good geologist’s hand lens. I use this one that I got on Amazon.

Some of the coloration in coquina comes from its cement. There are three primary cement types: silica, calcite, and iron oxide.

Silica and calcite are general very light in color or even colorless. They are also the most common types of cement. Iron oxide, however, is rust-red and often stains the sandstone to match. In coquina, the cement is almost always made of calcite (calcium carbonate), adding to the whiteish color.

Texture of Coquina

One of the defining features of coquina’s appearance is its texture. All coquina is clastic and fine- to medium-grained, meaning that it is made up of fragments and that those fragments range in size from about 1/16 mm and above.

These fragments are visible to the naked eye, but if you really want to get a good look at them I would highly recommend a good geologist’s hand lens. A nice hand lens is a really fun and useful tool when making observations about any rock, but especially one like coquina.

While coquina’s defined grain size can vary quite a bit, there is much less variation when it comes to the shape of the shell fragments and how well sorted they are.

Coquina is almost always made of angular, poorly-sorted shell fragments. These fragments are freshly broken from their original shells and have not had the time or opportunity to break down and become smooth. The high-energy environment in which this occurs means that many different sizes of shell fragments can become mixed together.

How to Identify Coquina

By now you might be thinking that if coquina just looks like a bunch of broken shell fragments turned into a rock, then identifying coquina should be a trivial matter. While that is often the case, there is plenty of variation in coquina that may lead you do identify it as something else. As with any rock, it is important to take a more systematic approach when identifying coquina and its variants.

To identify coquina, observe the rock to verify that it consists of shell fragments. These fragments should be visible to the naked eye and will be cemented together into a rigid framework. The space between them may be empty or nearly completely filled with cement. Coquina reacts vigorously to an acid test.

Coquina is technically a variety of limestone, so it is easy to simply identify a piece of coquina as such. Limestones that contain a significant amount of fossils are typically referred to as ‘fossiliferous limestone’, but coquina is in another category all by itself.

You wouldn’t technically be wrong to call a piece of coquina ‘limestone’, but this is a case where you should be ‘more correct’. The amount of shell fragments that coquina contains places it in a category all by itself, and it should be classified as such.

This can become a little tricky if the pore space (empty space) between the shell fragments has been mostly (or even completely) filled in with calcite cement. This makes it more difficult to see all of the shell fragments and it isn’t as readily apparent that the entire framework of the rock is made from shells.

In general, if you can see a lot of shells and shell fragments that are in contact with one another to form a complete framework for the rock, then you can call it ‘coquina’. The cement between the shell fragments formed after the initial lithification of the rock, but the rock is still primarily made of shell fragment.

A rock must meet all of these requirements to be considered coquina:

- Clastic Sedimentary – Formed from the cementing together of rock and mineral fragments

- Fine- to Medium-grained – Individual grains range in size from 1/16 mm and above

- Angular Shell Grains – Sharp, angular shell fragments cemented together

- Reacts with Acid – Reacts vigorously with acid due to high amounts of calcium carbonate

A defining characteristic of coquina (and all limestone) is that it will react strongly to an acid test. I prefer to use common white vinegar to perform acid tests but in a lab setting you’d usually use a diluted hydrochloric acid solution (always take proper precautions with either). I have a video on how to perform this test (and others) in my Practical Rock Identification System.

If your rock meets all of those criteria then it is very likely coquina, or at least something very closely related. There are a few variations of coquina that you may want to become familiar with:

- Microcoquina – Very similar to coquina, but with smaller (under 2 mm) grains, best seen with a hand lens.

- Coquinite – Heavily cemented coquina, with pore space almost entirely filled with calcium carbonate.

These variants look noticeably different than pure coquina, but are closely related enough that it is usually sufficient simply to classify them simply as ‘coquina’.

Tip: This article is part of my sedimentary rock identification series. To read more about how to identify all igneous rocks, check out my article here.

What Is Coquina Made Of?

It might seem silly to even ask this question. We have already seemingly answered this question earlier in this article – coquina is made of shells and broken shell fragments, right? But the real answer can be a little more involved than that. So, what exactly is coquina made of?

Coquina is made from hard shells and shell fragments of shellfish like trilobites, mollusks, brachiopods, and other invertebrates. These shell fragments are made of calcium carbonate, and are usually cemented together by calcite. It is uncommon for coquina to contain notable amounts of sand, silt, or clay.

When you hold a piece of coquina, you’re holding the hard remains of hundreds or even thousands of shellfish that have been broken, transported, and turned into rock. It is a rock made almost completely out of fossils! These fossils are made of the mineral calcium carbonate, CaCO3.

The only part of coquina that isn’t made of these fossil shell fragments is the cement which binds them together. The cement is made of calcite, which is the most common form of calcium carbonate. So, while the cement is not a shell or fossil, it is essentially made of the exact same stuff as the shell fragments – all of which react with acid.

One of the defining features of coquina is what it’s not made from. Most clastic sedimentary rocks have some mixture of sand, silt, and clay-sized particles. But with coquina, this usually isn’t the case.

Coquina has a noticeable lack of any sand, silt, or clay. This is it forms in high-energy environments like beaches with strong waves. The strong currents of the water wash any small grains away, but aren’t strong enough to pick up the shell fragments.

This leaves the beach covered almost exclusively in broken shell fragments. If you have ever walked on a beach prone to large waves you have probably encountered this. The beach isn’t sandy, but there are larger pieces of sharp, jagged shell fragments that have been transported and broken apart by the wave action.

Where Is Coquina Found?

Coquina is such a cool-looking rock, you might be wondering where you can find a piece for yourself. Or maybe you’ve already found a rock that you think might be coquina and you’re wondering if your area actually has any to be found.

Unfortunately, coquina isn’t nearly as common as normal limestone or as other clastic sedimentary rocks. Still, there are plenty of places where it is known to occur in abundance, so you might be lucky enough to have one nearby.

In general, coquina is found along present-day coastlines in areas with a geologic history of rich marine life and high-energy environments such as tropical and subtropical beaches and barrier islands. In the U.S., you can find coquina on the Atlantic coasts of Florida and North Carolina.

One of the prerequisites for the formation of coquina is the presence of enough fossil material. The shellfish from which the shell fragments originate are most abundant in warm, tropical or subtropical waters, so it is only natural that coquina is most common near these warm locations.

But not every tropical beach forms coquina. The conditions have to be just right, with consistent waves strong enough to break the shells apart and sort them from sand and clay particles, but not so strong that they carry the shell fragments back out to sea.

Because coquina is often fairly fragile, most coquina formations are fairly young (geologically speaking). They will eventually weather away and be lost forever, or be transformed into something else entirely. This limits the number of places you’ll be able to find it, because it simply doesn’t last as long as many other rock formations.

You can look for coquina formations near you using this excellent interactive map from the USGS. I have a video about how to use this tool in my Practical Rock Identification System, plus even more information on how to identify coquina and other rocks.

How Does Coquina Form?

We’ve learned all about what coquina looks like, what it is composed of, and generally where it’s found, but I have only briefly touched on how it’s actually formed. The creation of coquina is a relatively straightforward process that always follows a few simple rules.

Coquina forms when shells are transported, broken, and sorted in high-energy marine environments like ocean beaches and barrier islands. These shell fragments are then covered and buried by new, younger sediment and undergo compaction, eventually becoming cemented together in a process called lithification.

When shellfish and coral die, they leave behind their hard remains. In warm, tropical settings, these shells accumulate in the shallow waters near beaches and barrier islands and they are transported by strong ocean currents and waves.

The shells eventually make their way to shore, where they are subjected to the constant beating of waves and tides. The shells are knocked into one another and abraded, eventually breaking them down in smaller and smaller fragments.

The energy from this process is enough to also pick up and carry away any sand and silt grains that may otherwise be mixed in with the shell fragments, leaving a very ‘clean’ collection of shell fragments all piled together in one location.

Over time, this collection of shell and coral fragments is covered by more sediment (perhaps more shells, or possibly sand and clay) and becomes buried. Given enough time, the weight of this overlying sediment compacts the shells fragments together.

Water is still circulating through the high-porous layer of shell fragments at this time. The water is laden with calcium carbonate, and over time it precipitates out of the water and deposits on the shell fragment grains in the form of calcite. This calcite eventually grows enough to cement the grains together, forming a coherent layer of rock.

The appearance of coquina will vary depending on the specifics of how these processes unfolded. Some coquina will have larger shell fragments than others. Some will be more tightly compacted, and the degree to which they are cemented together can vary greatly.

What Is Coquina Used For?

One of the reasons people may not be overly familiar with coquina is because you don’t often see it in day-to-day life. It is not a popular material for construction or decoration, and unless you live near a present-day shoreline you are unlikely to encounter it anywhere near you.

Coquina has, historically, been used as a construction material when the strength of the rock is not of importance. It is sometimes crushed to use as a filler material.

Perhaps the most famous use of coquina is in the construction of Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine, Florida. This Spanish fort famously sustained naval bombardment several times thanks to the use of coquina in its exterior walls. While coquina is not a strong material, it made for an unexpectedly resilient defense against cannon fire because it absorbed the impact of incoming cannon balls without entirely crumbling. The cannon balls simply embedded into the soft sides of the fortress without shattering!

This article is part of my rock identification series. To learn more about identifying rocks, check out my full in-depth guide here.