Almost everyone is familiar with limestone in some way or another. Chances are you have seen and held it yourself, even if you didn’t realize what it was at the time. It is one of the most common sedimentary rock types in the world and it comes in many different varieties. I thought it would be helpful to go over what limestone is and how to go about identifying it.

Limestone is a sedimentary rock made primarily from calcium carbonate, usually in the form of calcite and aragonite. Its grains vary in size and can consist of a variety of materials including shells, coral, and mud. It is typically off-white to gray in color and usually forms in shallow marine environments.

While limestone is a clearly defined rock type, it can still be difficult to know whether a rock you’ve found is actually limestone. It can easily be confused for similar, closely related rocks, and comes in so many varieties that one specimen can look quite different from another. I’ll walk you through how to identify limestone, what different varieties look like, and where it can be found.

What Does Limestone Look Like?

Limestone comes in so many distinct varieties that it can be difficult to describe what it looks like. One piece of limestone might look almost entirely different from the next, depending on how it was formed and where you found it. Still, there are general attributes that almost all limestones share if you know what to look for.

Limestone is usually off-white to gray in color, but may also have tinges of yellow, brown, or pink. Many varieties of limestone are massive with little to no identifying features, while others are almost entirely composed of shells and fossils and may contain other features like nodules and bedding planes.

While all limestone fits this general description, there is still quite a bit of variability from location to location. The size and type of grains are perhaps the biggest contributors to textural variability, while mineral impurities are the biggest driver of color.

Pro Tip: I have created the best rock identification system you’ll find anywhere. It’s made to help everyone from brand new hobbyists to university Geology students, and includes an eBook, digital tools, a video tutorials. Find out more here!

Varieties of Limestone

Because there is so much variation in limestone, it is perhaps easiest to briefly describe what each individual type looks like. Each of these varieties forms in a slightly different way, and it can have a drastic impact on what the final rock looks like.

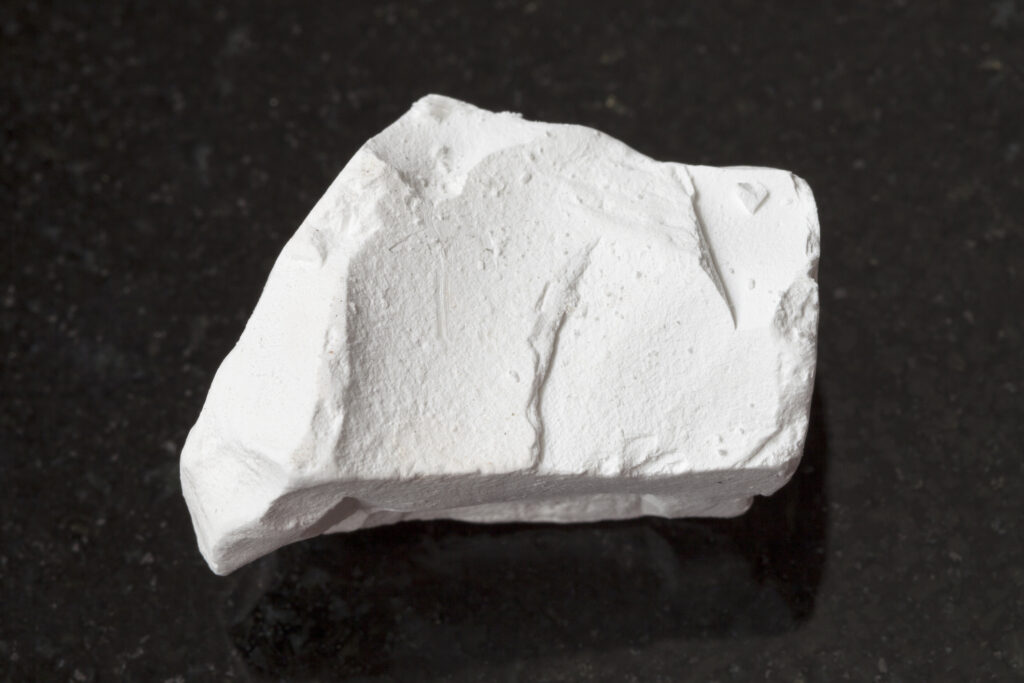

Chalk

Natural chalk is a very soft, porous, and light-weight variety of limestone with an earthy texture. It is formed from large amounts of the remains of microscopic organisms (usually plankton) collecting on the sea floor. It is usually almost pure white, and can be crushed in your hand.

Dense Limestone

This is a bit of a catch-all term for ‘normal’ limestone. It is massive and fairly dense, formed in common shallow-marine settings. It is usually off-white or light gray, may or may not contain visible fossils, and is composed almost entirely of calcite with some impurities like silica and iron oxide.

Crystalline Limestone

When limestone is subjected to heat and pressure, the calcite will begin to reorganize itself and crystallize into larger, visible crystals with little to no porosity between them. This is low-grade metamorphism, and it technically changes the limestone into another kind of rock – marble. It still reacts with acid and will usually retain much of the same off-white coloring as the original limestone, but if enough impurities are present it can be other colors including pink, red, gray, or even black.

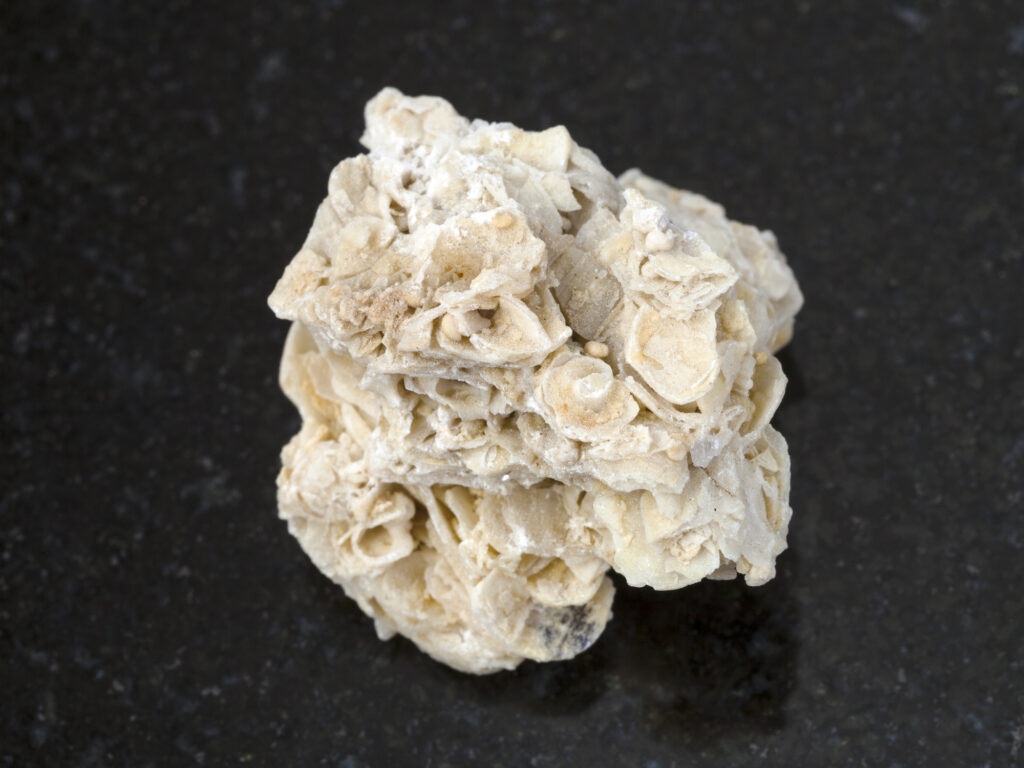

Coquina

Coquina is a variety of limestone that looks like shells and broken shell fragments fused together. This mass of shell fragments is loosely cemented together, often with a great deal of space (porosity) between them. Coquina inherits its color from the shells from which it is formed and is almost always white, off-white, or light gray.

Micrite

Micrite is essentially a ‘lime mud’. It is very find grained with particles too small to see even with a hand lens. It often has a smooth-feeling surface, sometimes with conchoidal fracturing. It is usually light gray or brown, and can sometimes be confused for chert.

Travertine & Tufa

This variety of limestone forms when calcite-rich water evaporates, leaving behind the calcite to grow into formations like stalactites and stalagmites. This process results in very dense limestone and is often recognizable for its unique shapes. Similarly, Tufa is a type of travertine that forms around hot springs with hot, calcite-rich water evaporates and creates highly porous rings.

Oolite

Oolite is one of the most unique-looking varieties of limestone. It looks like many small, round pellets cemented together. These pellets, called ‘ooids’, are formed when calcite precipitates out of water directly onto grains (usually silica) and grow in high-energy environments. The become cemented together by calcite and often display bedding planes and a preferred orientation.

Color is Driven by Mineralogy

Limestone is, in general, a very ‘pure’ rock in the sense that it is almost entirely comprised of calcium carbonate in the form of calcite or aragonite. This, in turn, means that almost all limestone you encounter will be whitish or off-white. However, there are some common impurities that can have a significant impact on the color of limestone if they are present in high enough quantities.

Manganese and iron are both fairly common impurities that can give limestone a yellowish, pink, or even rust-red color. While not common, limestone can sometimes be dark gray or even black if it contains enough organic material.

Sometimes you’ll find a piece of limestone that appears to be streaked with different colors. This is usually from iron, manganese, or magnesium staining the rock after it has already been formed. Water, laden with these minerals, seeps through the limestone and stains the white limestone in different colors, depending on what minerals are present at the time.

Pro Tip: To get a better look at the crystals in your rocks and help with identification I highly recommend picking up a good geologist’s hand lens. I use this one that I got on Amazon.

Texture of Limestone

As discussed above, the texture of limestone is highly variable depending on the type of limestone you’re looking at. Properly identifying the texture of a limestone is an integral part of determining the variety you’ve found, and there are a couple of well-known classification systems that geologists use to accomplish this.

The Folk Classification Model looks at the grains, matrix, and cement of limestone to describe and classify a specimen, while the Dunham Classification Model focuses on the composition and proportions of grain types.

It is not usually necessary for amateurs to use (or even be familiar with) these classification methods. It is almost always sufficient for enthusiasts to be able to recognize their rock as one of the limestone varieties listed above, or even simply as ‘limestone’. The Folk and Dunham classification models are used for more descriptive, scientific work where the details of the rock’s composition and texture are more important.

How to Identify Limestone

By now you might be thinking that identifying limestone must be incredibly difficult. While the wide variations seen in limestone can make the task challenging, in most cases it is still a relatively straightforward process. As with any rock, it is important to take a systematic approach when identifying limestone and its variants.

To identify limestone, first look for its characteristic white, off-white, or light gray color. It is relatively soft and can be scratched with a penny, but will usually scratch your fingernail. Limestone will react and fizz with a weak acid like white vinegar. Fossils, shell fragments, and coral are common.

Because the overall appearance of limestone is so varied from one specimen to the next, physical tests are often the best way to identify it. These tests are designed to give an indication of the mineralogy of the rock, and in the case of limestone we are testing for the presence (and abundance) of calcium carbonate in the form of calcite.

One of the best identifying features of limestone is its hardness. Since it is almost entirely made of calcite, limestone has a very similar hardness of around 3 on the Mohs hardness scale. This means that if you try to scratch the surface with a penny, some of the rock should be scratched away. If you see some of the copper being left on the surface of the rock, then that means it’s harder than the penny and it is not limestone. Similarly, if you find a sharp edge of the rock and press firmly while scratching your fingernail, it should leave some scratches.

Perhaps the most diagnostic method for identifying limestone is an acid test. I go into detail about how to safely perform this test with common white vinegar in my Practical Rock Identification System. Calcite will react vigorously to a diluted hydrochloric acid solution, especially when you scratch or powder it first. This reaction is a great way to tell the difference between limestone and dolomite, which only reacts weakly to acid.

The presence of fossils (especially marine fossils like shells and coral) are a great indication that you’ve found limestone. Fossils are also present in other types of sedimentary rocks like sandstone and shale, but are most prevalent in limestone. The amount of fossils you see in the rock can also help you determine the type of limestone you have. For instance, if the rock is almost entirely made up of shell fragments you have a piece of coquina.

In summary, a rock must meet all of these requirements to be considered limestone:

- Biochemical or Biochemical Sedimentary – Formed from the hard remains of marine animals and/or the precipitation of calcium carbonate out of water

- Very Fine- to Coarse-grained – Individual grains can be almost any size, ranging in size from microscopic to over 2 mm

- Reacts with Acid – Reacts vigorously with acid solution due to high amounts of calcium carbonate

If your rock meets all of those criteria then it is very likely limestone, or at least something very closely related. There are a few closely related rock types that you might confuse for limestone, so it helps to know what they are and how they differ.

- Marble – Metamorphosed limestone, with larger and more organized calcite crystals than normal limestone.

- Dolostone – Very similar to limestone, but made of dolomite instead of calcite. Slightly harder and often has a reddish hue.

- Diatomite – Often confused for chalk, but is very powdery and made of tiny silica particles instead of calcium carbonate.

What Is Limestone Made Of?

We have already seemingly answered this question earlier in this article – limestone is made of calcium carbonate – specifically in the form of calcite. But the real answer can be a little more involved than that. So, what exactly is limestone made of?

Limestone is made from calcium carbonate in the form of calcite or aragonite, sometimes with minor amounts of magnesium. It is common for limestone to form as aragonite before converting to calcite. Fossils are a common building block of limestone. Sand, silt, and clay are sometimes found in minor amounts.

Limestone is, by definition, almost entirely made up of calcium carbonate. The form of calcium carbonate can vary and is often a mix between aragonite and calcite, although calcite is far more common.

Sometimes, the calcium carbonate in limestone is gradually transformed and replaced by dolomite. This happens when there is a great deal of magnesium present, and usually gives the rock a slightly reddish color. It is also a bit harder than normal limestone. Some magnesium can be present in limestone before it is completely transformed into dolostone.

Tip: This article is part of my sedimentary rock identification series. To read more about how to identify all igneous rocks, check out my article here.

One of the defining features of limestone is what it’s not made from. Most clastic sedimentary rocks have some mixture of sand, silt, and clay-sized particles. But with limestone, this usually isn’t the case.

Some limestones have clastic material like sand, silt, or clay worked into their matrix, but it is usually only in minor amounts.

The fossils that are so often found in limestone are made of the same material the rest of the rock is made from – calcium carbonate. These shells are the hard remains of marine life that stick around long after the animal has died, and often help to form the fabric of limestone layers.

Where Is Limestone Found?

You might be wondering where you can find a piece of limestone for yourself. Or maybe you’ve already found a rock that you think might be limestone and you’re wondering if your area actually has any to be found.

Fortunately, limestone is an extremely common and prolific rock type. Something around 25% of all sedimentary rocks are a version of limestone. There are limestone outcrops all over the world, and chances are you can find some near you.

In general, limestone is found in areas with a geologic history of rich marine life and high concentrations of calcium carbonate in warm, shallow marine environments, such as tropical and subtropical reefs. Areas with a history of evaporites such as caves and hot springs are also likely to contain limestone.

Most limestone is thought to have been produced primarily as a byproduct of the remains of living things (biochemical). So, naturally, one of the prerequisites for the formation of most limestone is the presence of enough fossil material. The organisms from which the detritus originate are most abundant in warm, tropical or subtropical waters, so it is only natural that limestone is most common near these warm locations.

Limestone is pretty common to find in outcrop. This is because it tends to be more resistant to weathing than most other sedimentary rocks. Limestone is famous for its karst topography, which is essentially a very erratic and weathered surface marked by many cracks and joints.

You can look for limestone formations near you using this excellent interactive map from the USGS. I have a video about how to use this tool in my Practical Rock Identification System, plus even more information on how to identify limestone and other rocks.

How Does Limestone Form?

We’ve learned all about what limestone looks like, what it is composed of, and generally where it’s found, but I have only briefly touched on how it’s actually formed. The creation of limestone is a more complex and variable process than that of other sedimentary rocks.

Most limestone is formed from the deposition of the hard remains of marine life, but can also form from the direct precipitation of calcium carbonate out of warm water. The calcium carbonate, usually in the form of calcite, is then buried, compacted, and eventually cemented together to form limestone.

When shellfish and coral die, they leave behind their hard remains. In warm, tropical settings, these remains accumulate in large amounts. Sometimes this is in the form of coral reefs or something as simple as mounds of mud, but it has changed over geologic time.

Limestone sometimes forms almost entirely without the aid of living organisms. This type of limestone is a chemical sedimentary rock (as opposed to biochemical). It forms because ocean water is oversaturated with calcium, and in the right settings that calcium precipitates out of the water to form calcium carbonate. Warm, shallow water where this process is mostly likely to occur because the conditions are just right.

These types of marine limestones are then subjected to the normal process of diagenesis, which is the process sediments are turned into rocks. They are gradually buried by new sediment, compacted by the weight of the sediment and water above them, and then gradually cemented together by the minerals present in circulating water.

Another, more distinct method by which limestone forms is precipitation in evaporite depositional environments. This simply means that calcium-laden water is exposed on the surface in places like caves and hot springs, and when the water evaporates away the calcium is left behind. The slow accumulation of that calcium forms limestone varieties like travertine and tufa. You are likely familiar with stalactites and stalagmites, which are made of travertine.

What Is Limestone Used For?

Limestone is one of the most widely used rock types around the world. It has many practical applications, and since it is so common and widespread it has been used by cultures everywhere for a variety of purposes.

In general, limestone is used extensively for construction in the form of building stones, aggregate material, cement mixing, and chalk. It is very popular as an artistic medium, especially in the form of marble. Limestones have great economic value as oil and gas reservoirs and for commercial mining.

Limestone is so popular as a building material because it is easy to cut to desired dimensions, and is relatively soft while still being durable. In modern times, however, many limestone buildings have seen extensive damage due to acid rain which gradually eats away at the rock.

As a geologist working in oil and gas, I have overseen the drilling of many wells targeting limestone formations. Limestone can be extremely porous and can make for very attractive targets not only for oil wells but also for fresh drinking water.

This article is part of my rock identification series. To learn more about identifying rocks, check out my full in-depth guide here.