Phyllite is a widespread metamorphic rock, found in locations all over the world. Chances are good that you have seen and touched several times in your life, whether or not you were aware of it at the time. It is a very attractive and unique-looking rock, but it doesn’t have many practical applications when compared to most other rock types.

Phyllite can sometimes be fairly difficult to identify, partly because some people aren’t overly familiar with it and partly because it is often confused for other rock types. This is perfectly understandable because many rocks can superficially look very similar and share many of the same physical properties. It can be difficult to know exactly what phyllite looks like and how to identify it, but it is relatively simple if you know what to look for.

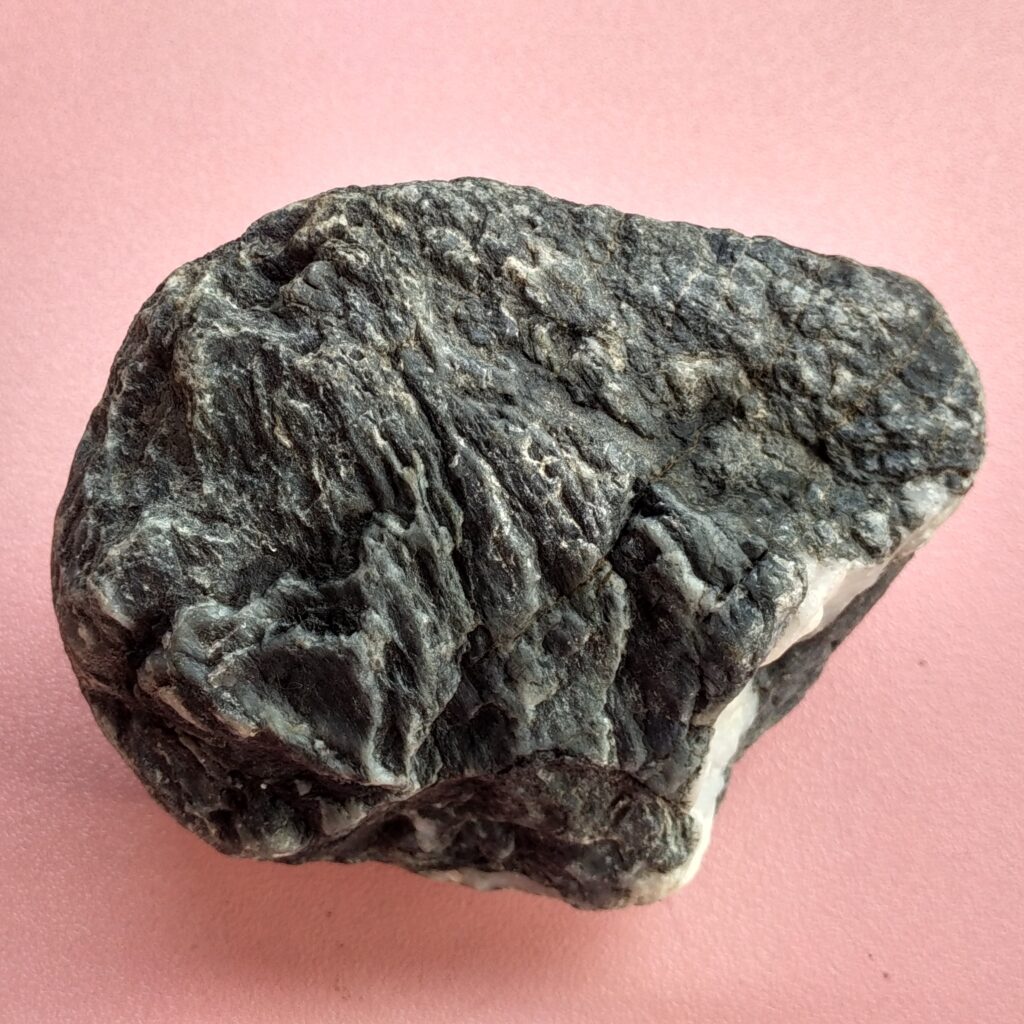

Phyllite is a fine-grained foliated metamorphic rock primarily made of quartz, chlorite, and mica minerals like muscovite and sericite. Known for its characteristic silky sheen, it often appears wavy or crinkled and tends to easily split into thin sheets. Phyllite forms from the continued metamorphism of slate.

While phyllite is a clearly defined rock type, there are many different varieties and closely related rocks that can make it difficult to confidently identify. I’ll walk you through how to identify phyllite, what it looks like, and where it can be found.

What Does Phyllite Look Like?

It can often be very difficult for people to identify phyllite, even with pictures and descriptions to compare to. This is mostly because phyllite isn’t primarily defined by its mineralogy, but rather by its texture.

In everyday life, it is relatively unimportant to be able to distinguish between phyllite and other similar-looking rocks, so people often just dismiss the exercise entirely. But if you’re actually interested in geology and knowing what kind of rock you’re looking at you probably want to be more specific than that. So, what does real phyllite actually look like?

Phyllite is fine-grained, made of minuscule mineral crystals invisible to the naked eye. Its foliation often appears wavy and the surface has a distinct silky sheen. Phyllite can easily be split into thin sheets. It is usually gray, black, or greenish gray. Larger crystals of minerals like garnet may be present.

Phyllite can be composed of many different types of minerals but is primarily made of quartz and platy minerals like micas and chlorite. Phyllite is not defined by its mineralogy so much as it is by its phyllitic texture.

While phyllite doesn’t have a strictly defined mineral composition, in practice there are some minerals that are almost always found in abundance. Quartz and platy minerals like muscovite, chlorite, and graphite are the most common minerals in phyllite, but the mineral grains are too small to see with the naked eye. However, you may be able to see some individual grains with the aid of a powerful hand lens like this one.

While all phyllite meets this general description, there is a pretty wide spectrum of phyllites that can look significantly different from one another. The difference in their appearance is driven by the mineralogy of each type of phyllite.

Texture of Phyllite

Since a phyllite is primarily defined by its texture, it first helps to know what phyllitic texture looks like.

Phyllitic texture is a form of low-grade metamorphic foliation. It describes the preferential orientation of very small crystals of platy minerals in a rock, giving it a silky luster and making it easy to break the rock along those planes.

I’ll dive deeper into how phyllite forms later in this article, but phyllitic texture occurs when very fine-grained mudrocks like shale are compressed during low-grade metamorphism. These rocks first metamorphose into slate, but increased temperature and pressure turn them into phyllite.

One often-overlooked aspect of phyllitic texture is crystal size. In order for a rock to be considered phyllite, you shouldn’t be able to see individual crystals with the naked eye. If you can see the crystals then you may very well be looking at schist, which forms from higher degrees of metamorphism.

Similarly, phyllite has not yet developed visible alternating bands of minerals like quartz and feldspar. A banded texture like that is known as gneissic and is the next phase of metamorphism beyond schist. Phyllite looks like a homogenous mass of silky and crinkled rock with no visible layers or banding.

Color is Driven by Mineralogy

The variation in the mineralogy of phyllite means that it can come in several colors. The dominant platy mineral often has the biggest impact on color, but it is also affected by the amount of quartz, feldspar, and other accessory minerals present in the rock.

Most phyllite is light or dark gray. It gets this color from the mica minerals from which it is usually formed – namely, muscovite or sericite. When combined with tiny quartz crystals, which are usually off-white or translucent, the rock ends up with a rather nondescript gray color.

Chlorite has a distinct green color and is sometimes a major component of phyllite. Many other colors are possible including off-white (talc) and dark silver (graphite). Phyllite can take on many colors depending on the relative abundance of these, and other, minerals. Even a small change in their relative amounts can have a drastic impact on the phyllite’s color.

How to Identify Phyllite

Even with a clear picture in your mind of what phyllite is supposed to look like, it can sometimes be difficult to identify. I think this is mostly because people aren’t as familiar with phyllite as they are with its close cousins (slate and schist). As with any rock, it is important to take a systematic approach when identifying phyllite.

To identify phyllite, first ensure that you cannot see individual mineral grains with the naked eye. Look for a silky, reflective sheen with a foliated texture that often appears wavy or crinkled. It should be easy to break off thin sheets or slabs from the rock. Phylite is usually light to dark gray or greenish.

A rock must meet all of these requirements to be considered a phyllite:

- Metamorphic – Formed from physical and chemical changes caused by heat and pressure

- Fine-grained – The grains of the rock matrix are not visible to the naked eye but visible with a hand lens

- Phyllitic Texture – Foliated, with preferential orientation of platy minerals. Silky, reflective surface.

If your rock meets all of those criteria then it is almost definitely phyllite, or at least something very closely related.

Phyllite is part of a continuum of metamorphic rocks, beginning at slate and ending with gneiss. As a rock is metamorphosed, it first changes into slate and then grades into phyllite, which grades into schist, which grades into gneiss. It can often be difficult to draw the line between these rock types. In these cases, just make all the observations you can about your rock and then decide on a classification for yourself.

Always bear in mind that phyllite can occur in a wide variety of colors. Shades of gray are the most common due to its high mica content, but color green is also common. While rare, some shades of blue or silver are also possible. Don’t assume that a rock isn’t phyllite just because it isn’t gray.

Tip: This article is part of my metamorphic rock identification series. To learn about how to identify all metamorphic rocks, check out my article here.

When observing and identifying a rock like phyllite it can often be useful to use a hand lens like this one from Amazon. This allows you to see the small features in the rock more clearly and often helps you identify the specific species of minerals present in many rock types.

Even with these clear criteria for identifying phyllite, it is common for people to confuse it with different rocks types. There are a few rocks that look close enough to phyllite that they can easily confuse people, so it is useful to know what some of those closely-related rock types are called and what they look like.

Rocks that are often misidentified as phyllite:

- Shale – A very fine-grained, layered sedimentary rock made of clay minerals. Turns into slate when subjected to low-grade metamorphism.

- Slate – A foliated metamorphic rock that is a precursor to phyllite, but is very fine-grained with no silky sheen.

- Schist – A foliated metamorphic rock that forms from the further metamorphism of phyllite with large, visible grains.

Like most rocks, phyllite can become very weathered when exposed to the elements. This can make it hard to identify because the colors can change significantly (usually to brown or rust-red) and many of the features become more difficult to see. When making any rock identification it is usually best to break off a piece of the rock (if you’re able) and look at a fresh surface.

What Is Phyllite Made Of?

Even though phyllite is primarily defined by its texture, its mineralogy is usually fairly consistent from one type to another. Phyllite forms only in a certain metamorphic setting and the end result always looks pretty much the same.

In general, phyllite is made from minuscule crystals of quartz, feldspar and platy minerals like muscovite, chlorite, and graphite. Smaller amounts of bulky metamorphic minerals like garnet and staurolite are common, sometimes as relatively large inclusions called porphyroblasts.

The vast majority of the total volume of phyllite is quartz and platy minerals. The thin sheets of these platy minerals make up the matrix (the main part of the rock) that binds any other minerals together.

The crystal grains in phyllite are generally too small to see, as are the cleavage planes along which it breaks. However, under magnification, you would be able to see countless thin laminations of platy minerals. It is along these boundaries that phyllite breaks into sheets.

It is common to do an acid test on rocks during the identification process to check for the presence of calcium carbonate. A weak hydrochloric acid solution will react and fizz on the surface of a rock if calcium carbonate is present. Phyllite will not react with acid because you will almost never find a phyllite with enough calcite in its composition. If your rock reacts with hydrochloric acid, it is not phyllite.

Where Is Phyllite Found?

Phyllite is a very common rock in the Earth’s crust and one of the most abundant metamorphic rocks you can find. It is created by the regional metamorphism of very common rock types, so there is no shortage of material from which it can form. Still, phyllite isn’t present just anywhere. If you are looking for it, it helps to know the type of geologic setting to look in.

Phyllite is found in mountainous regions where metamorphic rocks have been exposed to the surface. The continental side of convergent plate boundaries are ideal, where rocks are exposed to heat and pressure and thrust upwards. If schist or slate is present, phyllite is also likely to be present nearby.

In order to find phyllite, you have to have a sense of the geologic settings around you. If you’re in an area with only young sedimentary rocks exposed on the surface, you have very little chance of finding phyllite. However, if there are areas near you with hills or mountains you are much more likely to be successful.

Phyllite is usually fairly high in quartz content and its minerals are tightly packed and fused together from the metamorphic process. This means that it is pretty hard and resistant to weathering. Once it is exposed to the surface it takes a long time for it to break down. Pieces of phyllite can survive in a river for great distances, which is why you can often find pieces downriver from its source.

You can look for phyllite formations near you using this excellent interactive map from the USGS. I have a video about how to use this tool in my Practical Rock Identification System, plus even more information on how to identify phyllite and other rocks.

You can also use your knowledge and intuition! If you see schist or slate, chances are that if you follow that formation one way or the other it will gradually grade into phyllite.

In the U.S., you can find phyllite in places like the Appalachian Mountains and in the Pacific Northwest. These areas have at one time or another undergone significant compression and mountain building which is ideal for creating the metamorphic environment necessary to make phyllite.

How Does Phyllite Form?

We’ve learned all about what phyllite looks like, what it is composed of, and generally where it’s found, but I have only briefly touched on how it’s actually formed. The creation of phyllite is a fascinating process that takes a specific combination of circumstances to occur.

Phyllite forms from the regional metamorphism of clay-rich rocks like shale, mudstone, and volcanic tuff. These rocks are compressed and chemically altered, first metamorphosing into slate and then into phyllite as their minerals reorient themselves perpendicular to the direction of maximum stress.

The first step in the creation of phyllite is the presence of a clay-rich protolith. In most cases, this is a sedimentary rock like shale or mudstone, but sometimes it can be a volcanic tuff where the volcanic ash forms a thick layer of bentonite. These clay minerals have the necessary chemistry to be transformed by heat and pressure into platy minerals like mica and chlorite. These clay-rich rocks are usually buried under many more layers of rock over millions of years of deposition.

Note: A ‘protolith’ is the original rock from which a metamorphic rock forms.

The next step to creating phyllite is compression. Tectonic forces in the Earth cause huge masses of rock to be pushed and squeezed together, creating enormous amounts of stress and heat. These conditions allow for the original minerals of the protolith to gradually reorient and transform into minerals that are more stable at higher pressures and temperatures.

A rock will first metamorphose into a slate before becoming a schist. The two rock types grade into one another and it is often difficult to draw the line where one ends and the other begins.

Phyllite gets its distinct texture from the preferential orientation of its platy minerals. This orientation is a result of the regional compression the rock is enduring. The platy minerals form perpendicularly to the direction of maximum stress because that is the orientation in which they are the most stable. It’s like if you took a box of loose confetti and then squeezed the confetti together. The bits of paper would flatten and align themselves perpendicular to the direction in which you are squeezing them.

This process is gradual, and if subjected to further pressure and heat the phyllite would continue to metamorphose into schist. The process of metamorphism will take a clay-rich protolith and turn it into very fine-grained slate, then fine-grained phyllite, and finally medium-grained schist. With further metamorphism, the schist will become gneiss.

What Is Phyllite Used For?

Compared to most rocks, phyllite sees very little use in our day-to-day lives. Slate and schist are both used extensively for a wide variety of applications, but phyllite has comparatively little value.

Phyllite lacks the structural strength to be used as a major component in construction, but it is sometimes used as a decorative stone for its unique silky appearance. You sometimes see it used as a facing stone, for flooring, or for gravestones.

This article is part of my rock identification series. I invite you to keep reading about how to identify rocks with my full in-depth guide here.