Shale is a rock that almost everyone is at least fairly familiar with. It is the most common sedimentary rock on Earth and it has a distinct appearance that often makes it easily recognizable. You often see it used for decorative purposes, and it has enormous economic value in the mining, construction, and oil and gas industries.

While most of us are familiar with shale, not many people know much about it other than what it generally looks like. There is actually a very specific set of criteria that a rock has to meet to technically be considered a ‘shale’. It can be difficult to know exactly what shale looks like and how to identify it, but it is relatively simple if you know what to look for.

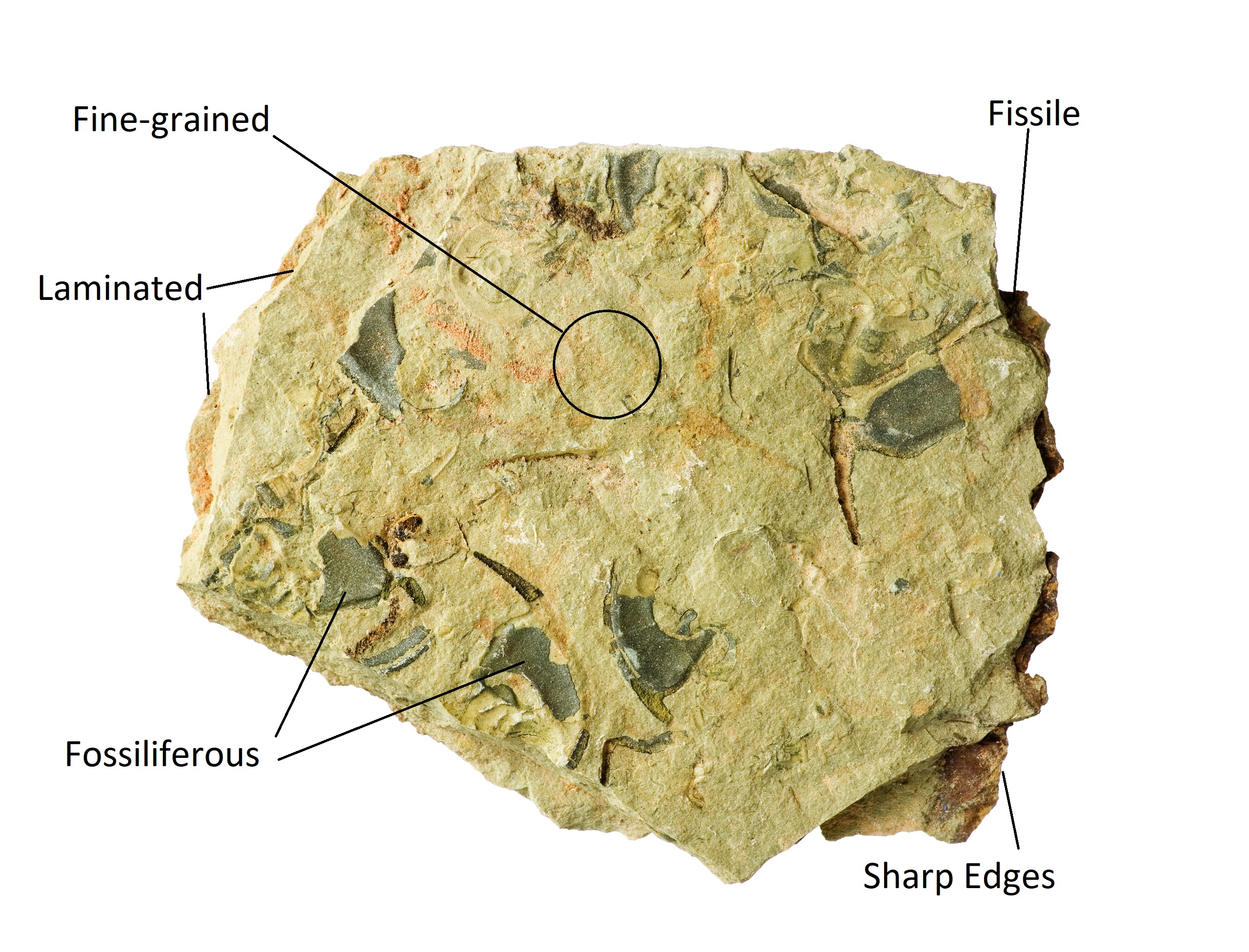

Shale is a fine-grained sedimentary rock composed primarily of clay minerals and other clay-sized particles of minerals like quartz and calcite. It is laminated and fissile, easily breaking along bedding planes. Shale forms from the deposition and compaction of clay-sized minerals in a low-energy environment.

While shale is a clearly defined rock type, there are many different varieties and closely related rocks that can appear quite different from one another. I’ll walk you through how to identify shale, what it looks like, and where it can be found.

What Does Shale Look Like?

When most people think of shale it is pretty easy to conjure an image of what it looks like. Most of us envision a dark gray rock with lots of thin, parallel layers, and that’s about as far as it goes. While that mental picture is fine, shale can look quite different than that – especially when it comes to color. So, what exactly does shale look like?

Shale is most often dark gray or black but can be almost any color including red, green, and brown. It is very fine-grained, made of particles invisible to the naked eye. It has a layered, laminated appearance with many thin, parallel beds. The edges of shale are usually sharp due to its fissile tendency.

While all shale meets this general description, there is a pretty wide spectrum of shales than can look significantly different from one another. This difference in appearance is primarily a result of varying mineralogy.

Color is Driven by Mineralogy

Since shale is made up of tiny flakes or particles of other rocks, its color is determined almost entirely by what minerals it is composed of and their relative abundance. Small changes in the percentages of minor minerals present can have a drastic effect on the color of a shale.

The dark gray or black color that is most often associated with shale is usually a result of its organic content. It takes only a small amount (think 2% of the total volume) of organic matter to give shale its characteristic dark gray color. This organic matter is often converted in kerogen, which is a precursor to oil and gas. A shale being this color is a good indicator that it was formed in an anoxic environment, meaning there was little to no oxygen present that would have destroyed the organic matter. This happens in deep, calm water like in the farthest extents of river deltas.

A shale can appear red if it has a large amount of hematite or other iron oxides. The shale may not have originally been this color, but over time the iron oxidizes and gives the shale a distinct rust-red color. Small amounts of other minerals can also give unique colors. For example, limonite will make shale appear yellow, and goethite will make it brown. Blues and greens are also common for shales with higher carbonate content.

Texture of Shale

The texture of shale is probably its most important defining characteristic. Shale is fine-grained, laminated, and fissile, which sets it apart from other clastic sedimentary rocks. It is important to know what each of these terms means and what they describe.

A sedimentary rock is fine-grained when it is made of particles you can’t see with the naked eye. Even with a hand lens, identifying the individual clay particles in shale may be difficult. All shales are fine-grained. If you can see some individual particles in your rock you may actually have a siltstone.

Perhaps the most telling textural feature of shale is lamination. It should be easy to spot thin, parallel beds that may or may not have slightly varying colors and textures. The rock will tend to break along those parallel bedding planes.

Speaking of which, the tendency for shale to easily break and crumble along its bedding planes is known as fissility. Shale is usually very fissile, which sets it apart from mudstone. Mudstone is very similar to shale, except it is massive instead of laminated and fissile.

How to Identify Shale

Shale is so widespread and relatively recognizable that you might think that identifying it is a trivial matter. While that is often the case, that mindset often leads people to misidentify other rock types as shale. It is important to take a more methodical approach when identifying a rock that you suspect might be shale.

To identify shale, first observe its grain size and ensure that no individual grains can be seen with the naked eye. Next, look for thin, parallel layers and note if the rock tends to break along those surfaces. Shale specimens usually have sharp edges, and it is common for fossils to be present.

A rock must meet all of these requirements to be considered a shale:

- Clastic Sedimentary – A rock formed from the compaction and cementation of other rock fragments

- Fine-grained – Grains are too small to see with the naked eye

- Laminated – Thin, parallel beds that extend throughout the rock like sheets of paper

Many (but not all) shales also have the following characteristics:

- Fissile – The rock tends to easily break along the laminated bedding surfaces

- Fossiliferous – Fossils are present

If your rock meets all of those criteria then it is a shale, or at least something very closely related. Remember that not all shales contain fossils, and that some of them are well-cemented enough so as not to be fissile.

Tip: This article is part of my sedimentary rock identification series. To learn about how to identify all sedimentary rocks, check out my article here.

Always bear in mind that shale can occur in a wide variety of colors. Dark gray and black are the most common due to organic content, but colors like brown, off-white, red, green, and blue are common. Don’t assume that a rock isn’t shale just because a rock isn’t dark gray.

When observing and identifying a rock like shale it can often be useful to use a hand lens like this one from Amazon. This allows you to see the individual grains and internal structures more clearly, and often helps you identify the specific species of minerals present in a rock.

Even with these clear criteria for identifying shale, it is common for people to confuse different rocks types for shale. There are a few rocks that look close enough to shale that they can easily confuse people, so it is useful to know what some of those closely-related rock types are called and what they look like.

Rocks that are often misidentified as shale:

- Slate – A low-grade metamorphic rock often formed from shale. Is often hard, and rings when struck.

- Siltstone – A clastic sedimentary rock similar to shale but with slightly larger, visible grains.

- Mudstone – Very similar to shale, but with no visible laminations (massive).

It is common to do an acid test on rocks to check for the presence of calcium carbonate. A weak hydrochloric acid solution will react and fizz on the surface of a rock if calcium carbonate is present. Unfortunately, this test isn’t all that useful in determining if your rock is a shale because, depending on mineralogy, some shales will react with acid and others won’t. However, if you already know it’s a shale it can tell you if calcium carbonate is present, either as cement between the grains or as some of the grains themselves.

What Is Shale Made Of?

Now that you know what shale looks like and how to identify it, you’d probably like to know more about it. Since shale is largely defined by its grain size, it can be composed of a pretty wide variety of minerals and rock fragments. Shale is not defined by its mineralogy, but because of the way it forms it is almost always made from only a handful of possible components.

Shale is primarily made from clay minerals like kaolinite, illite, montmorillonite, and smectite, with significant amounts of clay-sized particles of minerals like quartz, calcite, and feldspar. Small amounts of iron oxides and organic matter (sometimes converted to kerogen) are often present, as are fossils.

The relative amounts of a shale’s components depends heavily on the type of material present during deposition. The minerals that form a shale will be representative of the source rock from which they came – if not in their original form then in a chemically altered version.

A typical shale contains about 60% clay minerals and 30% clay-sized quartz particles. The bulk of the remainder is usually some combination of feldspar and calcite, with small amounts of organic matter and iron oxides.

As discussed above, the color of shale can often tell you something about its mineralogy. Without expensive laboratory testing it is nearly impossible to get an accurate breakdown of a shale’s makeup, but observing the color can be helpful. If a shale isn’t dark gray or black then that likely means it is almost entirely devoid of organics. A reddish or greenish color indicates higher percentages of iron oxides in varying states of oxidation, while a blueish color often means there are more carbonates present.

Where Is Shale Found?

Shale is the most common sedimentary rock type found on the surface of the Earth, accounting for approximately 70% of sedimentary rocks. But as widespread as shale is, you can’t find it just anywhere.

Shale is most commonly found in areas where ancient seabeds have been uplifted and exposed on the surface, usually interbedded in large packages with other sedimentary rocks like limestone and shale. They typically occur over large geographical areas since they form in large, low-energy marine environments.

You will often hear about oil and gas companies drilling shales in places like Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, Texas, Colorado, and North Dakota. These oil-bearing shale targets are usually miles underground, but those same rock layers are often exposed on the surface somewhere not too far from where they are being drilled.

Shale is pretty common in the United States and throughout the world. It can even be found in large mountain ranges thanks to tectonic forces driving ancient seabeds high into the sky. If you see other sedimentary rocks like sandstone and limestone, chances are you will also be able to find some shale nearby. Ancient fluctuations in sea level caused common patterns of interbedded shales, sandstones, and limestones to form all over the world.

How Does Shale Form?

We’ve learned all about what shale looks like, what it is composed of and generally where it’s found, but I have only briefly touched on how it’s actually formed. The creation of shale is a fascinating process that always follows a few simple rules that give shale its characteristic look.

Shale forms from the deposition and subsequent compaction and cementation of fine-grained sediments like clay and quartz. This process occurs in low-energy marine environments where small particles can settle out of the water, forming thin, parallel beds and often collecting the fossilized remains of marine life.

The defining characteristic of shale is its very fine grains. In order for these extremely small particles to settle out of the water there has to be very little current or turbulence. Think about when you try to stir a powder into a glass of water – when you first pour it in it just sinks to the bottom because there is no energy to circulated and suspend the powder in the water. But when you stir it up, the current picks up the powder and keeps it suspended in the water.

The same is true for sediment in running water. The clays and other fine-grained particles in a river remain suspended pretty easily. But when that river dumps into a large body of water like an ocean or sea, the current stops and the sediment drops out of the water column to the seafloor.

Larger particles like sand or cobbles require more energy to remain suspended in the water, so they drop out closer to the mouth of the river. This process separates the clay-sized particles from larger sediments, which is the reason shale sediments are so uniform in size. We call this characteristic ‘well-sorted‘ because there aren’t varying sizes of sediment.

Over time, varying degrees of sediment deposition (caused by storms, sea level changes, etc) cause many thin layers of clays to be deposited over one another. Living organisms swimming in the water above may die off and settle to the bottom to become fossilized within the sediment.

After enough time, these layers of sediment become compacted by the weight of the other sediment and the water above. Eventually, the grains become cemented together by silica or calcite and form shale. In many cases, this rock is later forced above sea level by tectonic forces and/or sea level changes.

What Is Shale Used For?

Shale is a very important rock for commercial and industrial use. You can also sometimes see it used for decorative or ornamental purposes. Most of its economic value is derived from its mineralogy, either for its large amounts of clay or organic matter.

Shale is most commonly used for the extraction of clay for use in cement, pottery, tile, and bricks. It also has enormous economic value for the oil and gas industry as a target for horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing. Shale is a common source rock for oil and gas due to its high organic content.

The extremely high clay content in shale makes it ideal for the manufacturing of things like tile, bricks, and pottery. These clays can be shaped and heated to create extremely hard and attractive pieces, useful for construction material or decoration. In combination with limestone, shale can be processed to create cement.

In the last few decades, shales have become the primary target of most oil and gas companies. Shales are what is known as a ‘source rock’, where organic content is converted into kerogen and, eventually, oil and gas. Almost all of the organic matter that eventually becomes oil and gas is held within shale.

Historically, it wasn’t possible or economic to target these rocks because their permeability was so low and there were significant challenges drilling them. However, with improved technology like horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing it became possible and highly economic to target these shales directly.

While you can sometimes see shale used for decorative purposes, it is far less common than most other rocks. Most shales weather and crumble easily, so they aren’t all that practical to use this way.

This article is part of my rock identification series. I invite you to keep reading about how to identify rocks with my full in-depth guide here.