Syenite is a rock that most people aren’t that familiar with. In many ways, it is very similar to granite, but it varies significantly in its composition and appearance. Identifying syenite can sometimes be a challenge, especially since it is relatively rare and you may not be familiar with what it looks like. However, identifying syenite is a relatively simple process once you know what to look for.

Syenite is an intrusive igneous rock composed primarily of alkali feldspar, lesser amounts of of plagioclase feldspar, and under 20% quartz. It is coarse-grained with tightly interlocking crystals. Syenite is usually off-white, gray, greenish, red, or pink with black spots and no layering or banding.

While syenite is a clearly defined rock type, there are many closely-related rocks that are considered a part of the syenite family. Syenite and its different varieties can also be easy to confuse with other igneous rock types. I’ll walk you through how to identify syenite, what it looks like, and where it can be found.

What Does Syenite Look Like?

Syenite is a fairly uncommon rock type, so it’s no wonder that most people aren’t familiar with what it looks like. Even if you have seen or held syenite at some point you may have misidentified it as some sort of granite, which is understandable because they can look very similar to one another. So, what exactly does syenite look like?

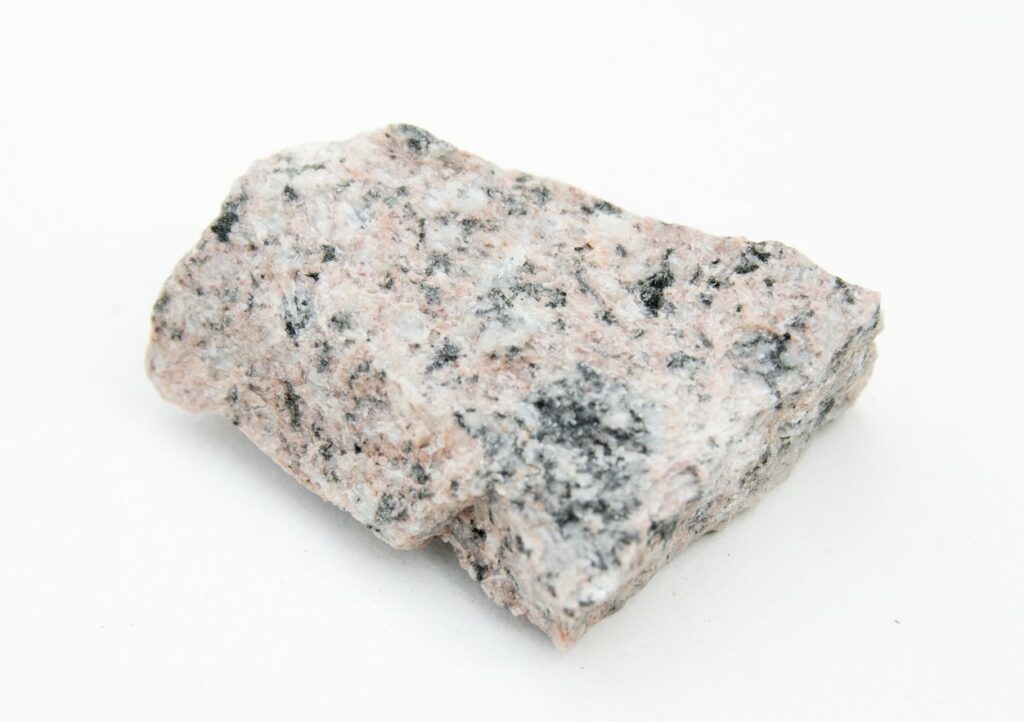

Syenite is a light-colored, coarse-grained igneous rock with crystals that are visible to the naked eye. It is commonly pinkish due to its high alkali feldspar content, with little quartz. Intermixed dark, mafic minerals often give syenite a ‘salt and pepper’ look. It lacks features like layering, banding, or fossils.

While most syenite meets this general description, there can be quite a lot of variation from specimen to specimen. The difference in their appearance is driven by the mineralogy of each type of syenite and, to a lesser extent, the subtle differences in their textures (crystal sizes).

Color is Driven by Mineralogy

The mineralogy of syenite is very similar to that of granite, but with notably less quartz content. True syenite has less than 5% overall quartz content, while some closely-related rocks like ‘quartz syenite’ can have slightly higher amounts – up to 20%.

The two major minerals present in all syenites are alkali feldspar and plagioclase feldspar. Each of these minerals can present itself in different ways. Alkali feldspar, in particular, can look quite different from rock to rock depending on the specific mineral species that is present.

Alkali feldspar is the most prevalent mineral in syenite, and therefore has the biggest impact on its color. There are several varieties of alkali feldspar, but orthoclose is the most common in syenite. Alkali feldspars can be many different colors, but usually, they are white, salmon pink, gray, brown, or greenish. More than one species of alkali feldspar can be present in the same piece of syenite, although they may be difficult to distinguish from one another.

Plagioclase feldspar is the second-most prevalent mineral in syenite. Like alkali feldspars, it can come in many different colors, but it is usually white or light gray. The crystals often have tiny grooves or striations on them. You probably won’t be able to see those in most syenites unless you have the aid of a good hand lens.

Both major feldspar types are a significant contributor to syenite’s overall light color. You won’t find any syenite that looks dark or black.

Quartz, while only occurring in small quantities, usually appears in syenite as translucent, light gray, or off-white. In polished countertops with significant quartz content (like granite) it sometimes feels like you can see below the surface of the rock. This is because the quartz crystals are transparent or translucent, allowing you to see through them. Some varieties may have more impurities which make the quartz crystals an opaque gray or white color.

The most common accessory minerals (generally under 15% of the total rock volume) in syenite are hornblende and pyroxene. These minerals are both very dark or black and can form relatively large crystals in the lighter-colored matrix. This gives syenite a speckled or salt-and-pepper appearance, but the light-colored minerals (predominantly feldspars) significantly outweigh the darker ones.

Texture of Syenite

One of the defining features of syenite’s appearance is its texture. All syenites are coarse-grained, meaning that you can see the individual crystals in the rock. This texture is known as ‘phaneritic’, and it forms when magma cools slowly and allows the crystals enough time to grow before becoming completely solidified.

While all syenites are phaneritic, it is also possible (and even common) to describe their texture in other ways. Rocks can be described as having more than one texture as long as the texture types are not mutually exclusive.

Most syenite is ‘equigranular‘, which means that all of the crystals are approximately the same size. So, a syenite rock may be described as ‘phaneritic and equigranular’ if you can see similarly-sized crystals with the naked eye.

Many syenites can have what is called ‘perthic‘ texture, and are sometimes even called ‘perthite’. This texture describes when two different types of feldspars intertwine and grow together, giving them a striated or feathered look, usually with alternating pinkish and white colors in a parallel orientation.

How to Identify Syenite

Syenite can be a very difficult rock to identify. It isn’t a rock type that most people are even familiar with, and it often looks like much more common rocks like granite. As with any rock, it is important to take a methodical approach when identifying syenite. Once you know what to look for, it is actually fairly easy to spot syenite and distinguish it from other rock types.

To identify syenite, look for overall light coloration note if you can see individual crystals with the naked eye. Try to identify large amounts of feldspars (especially alkali feldspar) with very little quartz, along with minor amounts of darker hornblende or amphibole. There should be no porosity or layers.

A rock must meet all of these requirements to be considered a syenite:

- Igneous – Formed from cooling magma. Interlocking crystal grains.

- Coarse-grained – Phaneritic texture with crystals visible to the naked eye

- Felsic Mineralogy – High feldspar content with lack of quartz, and under 15% dark minerals

- Massive – No internal structures or layering

If your rock meets all of those criteria then it is very likely a syenite, or at least something very closely related. Rocks with slightly varying mineralogy are sometimes still referred to as syenites or some derivation thereof. For example, ‘quartz syenite’ can have up to 20% quartz, and some syenites have more mafic (dark) minerals and are more intermediate in composition than felsic. However, for purposes of casual identification ‘syenite’ is usually close enough.

Tip: This article is part of my igneous rock identification series. To read more about how to identify all igneous rocks, check out my article here.

When observing and identifying a rock like syenite it can often be useful to use a hand lens like this one from Amazon. This allows you to see the individual crystal grains more clearly and often helps you identify the specific species of minerals present in a rock.

What Is Syenite Made Of?

As I mentioned above, syenite is largely defined by a specific mineralogy. All rocks are made from one or more minerals, and in order to fully understand a rock like syenite, you have to know what those minerals are.

Syenite is primarily made from large amounts of alkali feldspars like orthclase, with smaller amounts of plagioclase feldspar. In true syenite, less than 5% of the rock volume is quartz. Dark, mafic minerals like hornblende, amphibole, and pyroxene usually account for under 15% of the total rock volume.

While this definition is very specific, there are plenty of subtle variations and exceptions that are generally still classified as syenite or in the syenite family. The overall defining characteristic of syenite is felsic mineralogy with a lack of quartz. Without sophisticated methods for measuring mineral types and percentages, it is impractical or impossible for us to determine if a syenite-like rock falls into those specific percentage ranges, so it is sufficient to call anything reasonably close a ‘syenite’.

Still, it is useful to know what some of those closely-related rock types are called and what their mineralogy looks like.

Where Is Syenite Found?

Syenite is a fairly uncommon rock, especially when compared to is more well-known counterparts like granite. It only occurs in a few specific geologic settings, and is therefore not all that easy to find unless you know where to look.

In general, syenite occurs in areas with a history of igneous activity in thick continental crust where magma bodies and granitic protoliths undergo partial melting or fractional crystallization. In the U.S., syenite can be found in several places including New England, South Carolina, and Michigan.

Michigan is, perhaps the most popular destination for rockhounds looking for syenite, and they may not even know that it’s syenite they’re looking for! The variety of syenite pebbles found in Michigan are known as ‘Yooperlites’ and they are extremely popular with collectors because of their sodalite content, which lights up splendidly under a black light.

Because syenite forms beneath the surface of the earth, the vast majority of it isn’t visible or accessible to us. But, through the tremendous power of plate tectonics and erosion, some syenite is exposed on the surface, often near large granite bodies.

Syenite is composed of relatively hard minerals (feldspars) which make it incredibly durable. Once it is exposed on the surface it takes a long time for it to break down. Pieces of syenite can survive in a river for great distances, which is why you can often find syenite downriver from its source. In the case of Yooperlite, the rock fragments were carried great distances by glacial activity moving down from present-day Canada.

You can look for syenite formations near you using this excellent interactive map from the USGS. I have a video about how to use this tool in my Practical Rock Identification System, plus even more information on how to identify pegmatite and other rocks.

How Does Syenite Form?

We’ve learned all about what syenite looks like, what it is composed of and generally where it’s found, but I have only briefly touched on how it’s actually formed. The creation of syenite is a somewhat complicated process but it always follows a few simple rules.

Syenite forms from the slow cooling of felsic, quartz-deficient magma beneath the Earth’s surface. The magma is highly alkaline and lacking in quartz due to either partial melting or fractional crystallization. It intrudes into shallower rock and gradually cools, allowing the formation of visible crystals.

All igneous rocks form from the cooling and solidification of magma (or lava), and syenite is no exception. The magma from which it forms is highly alkaline and contains very little quartz. The process by which this relatively rare mixture occurs is not well understood, but it is thought to be a result of the partial melting of granitic rock.

Alkaline elements like potassium have a relatively low melting point, so they enter the melt before silica does. Once this melt begins to cool, it results in a rock with very high alkali feldspar content.

Because the composition of the source magma is never exactly the same from one syenite to another and the surrounding environment is always different, there can be quite a lot of variation in how the magma cools and the crystals form.

If the surrounding rock is relatively cool then the crystals formed on the edges of the igneous intrusion are likely to be smaller. In general, syenite bodies tend to be much smaller than those of granite.

As the individual crystals of syenite’s various minerals continue to grow as the magma cools, they eventually run into each other and they run out of room. Crystallization will continue until all of the magma is solidified, leaving behind interlocking crystals with virtually no porosity between them.

Because syenite forms as one solid mass, it contains no internal structures like bedding or banding. It looks the same from all directions and you can’t tell which direction was ‘up’ at the time of crystallization. This is called a ‘massive’ rock.

What Is Syenite Used For?

Syenite has many practical applications, both today and throughout history. It should come as no surprise that since syenite shares many of the same characteristics of granite, it is used in similar applications. Syenite has been in use for thousands of years for its durability, strength, and striking appearance.

Syenite is most commonly used for interior and exterior building applications. Highly polished syenite is a popular material for countertops, while rough-cut granite is one of the most prevalent components of buildings, bridges, and other structures.

Like most rocks, syenite is very strong in compression. This means it can withstand a great deal of ‘squeezing’ without breaking, making it ideal for use in construction projects with large overburden stresses.

What really sets syenite (and granite) apart is its ability to accept a polish and its resistance to weathering. Some of the highly polished ‘granite’ countertops you’re used to seeing may in fact be made of syenite and are made possible by the fact that feldspars are easily brought to a high shine. One of the biggest reasons syenite is so popular as a building material is because it doesn’t break down in the rain, ice, and wind as easily as other rocks.

This article is part of my rock identification series. To learn more about identifying rocks, check out my full in-depth guide here.