Sedimentary rocks are some of the most interesting and widespread rocks found in nature. When most people think of sedimentary rocks images of colorful sandstone layers in picturesque canyons come to mind, but there is a lot more to them than that.

There are many different types of sedimentary rocks, and if you know what to look for it can be fairly easy to identify them and distinguish them from other rock types. Sedimentary rocks are typically classified based first on the process of sediment deposition and then by grain size and composition. If you’re trying to identify a sedimentary rock it helps to know what they typically look like.

In general, sedimentary rocks display grains that are cemented together, often with visible layers, fossils, or unique features like mud cracks or ripple marks. Grain sizes can range from microscopic clays to large boulders. Sedimentary rocks may be almost any color depending on the source of the sediment.

Classifying rocks as ‘sedimentary’ is only the beginning. Sedimentary rocks come in so many distinct varieties that sometimes it can be hard to see how one is even remotely related to the other. I’ll go into how to further classify and identify sedimentary rocks, with pictures and descriptions of specific types.

How to Identify Sedimentary Rocks

Sometimes it can be very difficult to identify your sedimentary rock even with pictures and descriptions to compare it to, which is why it is usually best to take a methodical, step-by-step approach to the identification process. By going through this procedure you can almost always confidently arrive at a solid classification for your sedimentary rock.

To identify a sedimentary rock, first determine if it is clastic, organic, or chemical. If it is clastic, examine the sizes and shapes of the fragments to determine the rock type. If it is organic or chemical, determine the rock’s composition and look for unique characteristics to arrive at an identification.

This procedure might seem a little daunting at first, but it is actually quite simple. I’ll walk you through how to determine what type of sedimentary rock you have and then provide some helpful tables to ID your rock.

Pictures & Descriptions of Sedimentary Rock Types

There are so many types of sedimentary rocks that it can be hard to keep track of them all, but thankfully things are made a little easier by dividing them into three general groups. These groups are based on how the sedimentary rock is formed and, in general, all of the rocks within each group will tend to have similar characteristics.

I have listed and described many varieties of sedimentary rocks below, but not everyone agrees on certain definitions or classifications. For a lot of the rock types, there are also several sub-varieties that could easily use their own descriptions. For ease of reference and identification, I have kept things fairly general while still covering all the sedimentary rock types.

Clastic Sedimentary Rocks

Clastic sedimentary rocks are made up of little pieces of pre-existing rocks, compacted and cemented together to form a new rock. These rock fragments can vary greatly in size, from microscopic clay particles to very large boulders. The size and shape of these grains are largely determined by the source rock type and, more importantly, the distance and time they traveled before deposition.

Clastic sedimentary rocks are primarily classified by their grain size through the use of the ‘Wentworth Scale’. This scale simply gives concrete definitions to what size particles are considered a ‘sand’, ‘clay’, or ‘boulder’, for example. You can purchase cards like this one from Amazon to help you determine grain size, but usually this is just estimated by eyeing it.

It is very possible (and common) for clastic sedimentary rocks to contain more than one grain size. If there is a mix of grain sizes then it is ‘poorly-sorted’, and if all of the grains are uniform in size it is ‘well-sorted’.

After grain size, it is important to look at the shape of the grains. Grains with jagged edges are referred to as ‘angular’ while smooth grains are ‘well-rounded’. It is also common for geologists to describe the overall shape of the grains as having ‘high sphericity’ or ‘low sphericity.

By examining your clastic sedimentary rock and describing these features you can arrive at a solid general identification. Compare your clastic rock to the table and descriptions below and you will likely find a good match.

| Rock Name | Grain Size | Grain Sorting | Grain Angularity | Layering |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandstone | .06-2 mm | Poor to fair | Angular to subrounded | Usually visible |

| Siltstone | .004-.06 mm | Fair to good | Too small to describe | Not usually visible |

| Shale | <.004 mm | Good | Too small to describe | Usually visible |

| Mudstone | < .004 mm | Good | Too small to describe | Not visible |

| Conglomerate | >2 mm | Poor | Rounded to Subrounded | Not usually visible |

| Breccia | > 2 mm | Poor | Angular to Subangular | Not usually visible |

Sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock comprised of sand-sized particles about .1 to .2 mm in size. It is usually tan, brown, or reddish in color, and often (but not always) displays noticeable layers. The sand grains are most often made of quartz, cemented together by calcite or silica.

Sandstone is the most common and readily identified sedimentary rock, formed when sand grains are deposited, compacted, and cemented together. It is usually deposited in marine or fluvial environments.

Siltstone

Siltstone is similar to sandstone in most respects, but is distinguished by its smaller grains. It is comprised of particles smaller than sand grains but larger than clays. It may also contain a significant amount of clay particles, but will still feel fairly gritty to the touch. Siltstone can be almost any color but is usually tan, brown, or reddish in color.

Siltstone is an intermediate clastic rock between sandstone and shale, but it not as common as either. It doesn’t usually display visible layers, and will almost never break along bedding planes.

Shale

Shale is a clastic sedimentary rock comprised of clay particles which are too small to see with the naked eye. Due to the high clay content, shale is almost always light gray to dark gray in color. It is deposited in low-energy marine environments and therefore almost always displays distinct, noticeable bedding.

Shales are often ‘fissile’, meaning they tend to break very easily along bedding planes. They can be cemented together with silica or calcite. If they have calcite cement then it will react with a 15% solution of hydrochloric acid.

Mudstone

Mudstone is similar to shale in most respects, but can be differentiated by its lack of layers. While there isn’t one universally accepted definition of mudstone, it is made of always comprised of clay particles that are too small to see with the naked eye and is usually light gray to dark gray in color.

A mudstone will not break or crumble along bedding planes like a shale. Mudstones are formed from solidified, uniform muds that lack the layering seen in shales. They are more likely to be cemented with calcite compared to shales, and therefore more likely to react with a 15% solution of hydrochloric acid.

Conglomerate

Conglomerate is a clastic sedimentary rock consisting of varying sizes of rounded rock fragments. It is easily recognizable because it is usually made of many different types of rock fragments, giving it a disorganized and often colorful appearance.

Conglomerate forms in high-energy environments where many different rock sizes can be transported by moving water. The source of the rock fragments is usually far away from their eventual final destination, giving them time to be worn down and rounded in during transport.

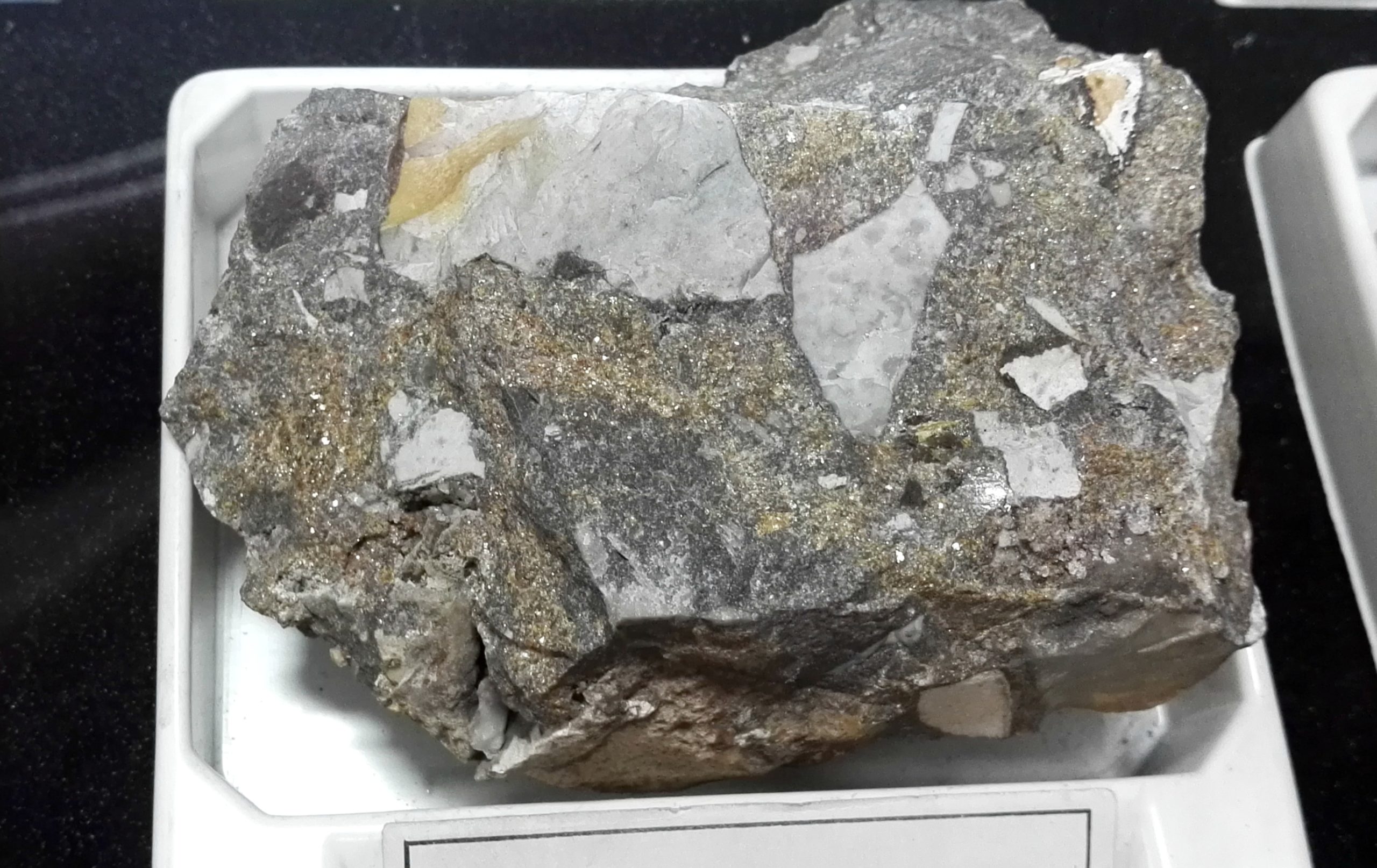

Breccia

Breccia is a clastic sedimentary rock formed from varying sizes of angular rock fragments. It is very similar to conglomerate with the notable exception of its angular grains. Breccia can be almost any color (and is often more than one color) based on the color of the sediment source.

Like conglomerate, breccia forms in high-energy environments where many different rock sizes can be moved by fast-running water. Unlike conglomerate, the source of a breccia’s rock fragments are very close to their deposition location, meaning that the broken rock fragments don’t have time to become worn and rounded.

Biochemical & Organic Sedimentary Rocks

Biochemical and organic sedimentary rocks are formed through the collection of particles associated with living things.

Biochemical rocks are formed when the secretions or remnants of living things (such as shells typically made of calcium carbonate) fall to the bottom of a body of water and are later compacted and solidified. The most prevalent and well-known example of this is limetone.

Organic chemical rocks are formed in much the same way, but instead of being formed from the hard remnants of living things they are comprised of the softer organic material. When soft organic material like plants die off and settle into low-energy water, that material can later be compacted and solidified into organic rocks such as coal.

Limestone

Limestone is a type of biochemical sedimentary rock formed from the hard detrital remains of living creatures. Shells or skeletal structures made of calcium carbonate accumulate on the seafloor when organisms die and become compacted and cemented together over time.

Sometimes the shells and structures are preserved in the limestone, but they may be destroyed and recrystallized instead.

Limestone is almost always an off-white to beige color, but impurities may give it a yellow, gray, or even blue hue.

There are quite a few distinct varieties of limestone including oolite, micrite, chalk, and travertine. All of these varieties are comprised of calcite, but vary in the size and shape of their shell fragments and how the calcite crystallizes.

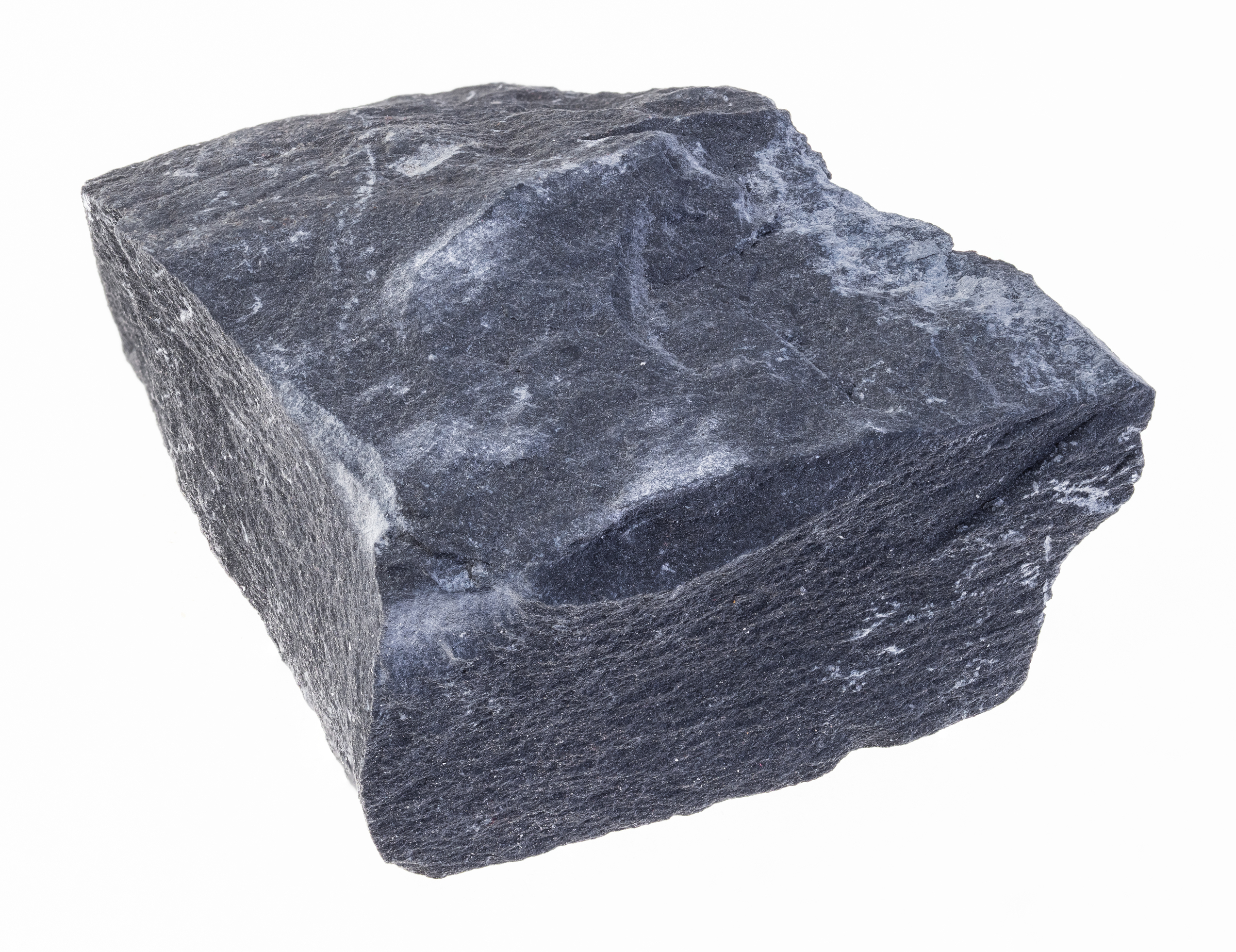

Coal

Coal is an organic sedimentary rock formed from the soft organic remains of living things. It requires a low-energy, oxygen-free depositional environment to form. Organic matter is compacted and solidified over time. Coal is formed primarily from soft organic matter, whereas limestone is formed from hard organic matter.

Coal is almost always dark gray to black in color, and depending on its quality and composition it can vary in hardness, brittleness, and luster. It is commonly mined for its economic value since most varieties can be readily burned for fuel.

Diatomite

Diatomite is an organic sedimentary rock formed from the fossilized skeletal remains of microscopic organisms known as diatoms. It is usually very loosely consolidated and high in porosity, meaning that it breaks apart very easily and is unusually lightweight for any given volume.

Diatomite is almost always off-white in color due to its silica composition. As diatoms (a type of algae) die off, they settle to the bottom of their body of water and their hard exterior cell walls accumulate to become diatomite. The most famous example is the White Cliffs of Dover. It is often ground up to form diatomaceous earth which is used for its unique absorbent qualities.

Chemical Sedimentary Rocks

Chemical sedimentary rocks are formed in a distinctly different way than clastic or biochemical sedimentary rocks.

Most chemical sedimentary rocks are formed when minerals precipitate out of large bodies of water that have dried up. These types of rocks are known as ‘evaporites’ because as the water evaporates it leaves behind all of the minerals it once contained. This process usually happens over a very large geographic area where large saltwater lakes once stood.

Dolostone

Dolostone, or dolomite, is a type of altered limestone, usually formed when large amounts of magnesium replace limestone before the rock is fully solidified. Dolostone is very similar to limestone in most respects and can be difficult to differentiate by the naked eye. It typically has very similar colors and textures compared to limestone, and forms in the same geological settings.

Dolostone can be easily differentiated from limestone by using an acid test. While limestone will readily react and fizz to a 15% HCL solution, dolostone will only give a weak reaction after freshly scratching the surface with steel.

Chert

Chert is a sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, meaning that the individual quartz crystals are too small to see. It is most often off-white to gray, but can be almost any color. It an often be identified by its sharp edges and conchoidal fractures.

Chert can be classified as either a chemical or a biogenic sedimentary rock, depending on how it forms. When chert forms through silica precipitating out of groundwater and solidifying, it is ‘chemical’. However, when it forms from the collection and solidification of microscopic silica remnants of living things it is ‘biogenic’.

Chert is extremely popular with rock collectors because of its wide variety of colors and sub-species. Some of the most well-known and popular varieties include agate, flint, onyx, and jasper.

Halite

Halite is a chemical sedimentary rock formed from the precipitation of salt out of solution. Also known as ‘rock salt’, it is often found in places like the Great Salt Lake Desert where ancient seawater with high concentrations of salt eventually dried up, leaving the salt behind. Rocks formed this way are known as ‘evaporites.’

Halite is usually colorless or white, but depending on impurities can be many other colors including shades of blue, red, and purple. These colors can often be seen in some higher-end ‘fancy’ table salts. While I generally advise against licking rocks for identification purposes, halite is the one rock type where I feel like it can definitely serve as a confirming piece of evidence.

Gypsum

Gypsum is an evaporite chemical sedimentary rock formed when sulfate minerals precipitate out of water. It is a very common rock type, and has several notable varieties including alabaster, selenite, and ‘desert roses’.

Gypsum is very soft, registering at a 2 on Mohs harness scale. It is often found in conjunction with other evaporites like halite in places like the Bonneville Salt Flats. Perhaps the most famous location in the U.S. is White Sands National Park where a rare form of gypsum sand is strewn of many square miles. Another fantastic place to search for gypsum selenite crystals (that I have personally had the pleasure of visiting) is Salt Flats State Park in Oklahoma.

Travertine

Travertine is a type of chemical sedimentary rock that is formed when calcite rapidly precipitates out of solution. It is usually associated with hot springs, forming unique ring formations, stalactites, or stalagmites.

Because of its chemical composition, it is technically a specific type of limestone. Travertine often displays visible banding as a result of alternating periods of hydrothermal activity. Smaller sections of travertine (removed from their place of origin) usually look very similar to other limestones.

How are Sedimentary Rocks Classified?

There is a bit of a paradox when it comes to classifying sedimentary rocks. In order to choose the proper means of classification you must first know something about the rock: is it clastic, biochemical, or chemical?

This is, seemingly, a chicken-and-the-egg situation. If you don’t know what type of rock you have, how can you narrow it down to the major sub-types of sedimentary rocks? In general, I find it useful to first classify the rock as ‘clastic’ or ‘other’.

If a sedimentary rock is clastic, it is classified by its grain size, grain shapes, and the composition of the grains. If the sedimentary rock is biochemical, it is classified by the composition of the biologic detrital material. If it is chemical, it is determined by the composition of the precipitated minerals.

Clastic rocks are the most readily identifiable sedimentary rocks because you can almost always see or feel the grains from which they are made. In clastic rocks like sandstone and conglomerate you can easily see the individual grains, and in shales and mudstones you can usually feel a gritty texture when you firmly rub the surface with your fingers.

Chemical sedimentary rocks tend to be made of a single mineral type (like halite or gypsum) because as the water from which they form evaporates the conditions are such that usually only one mineral will precipitate out at a time.

Biochemical sedimentary rocks often contain visible fossils, and because they are most commonly formed from calcium carbonate they often fizz under a hydrochloric acid solution. Limestone is by far the most common biochemical sedimentary rock and is generally easily identifiable. Less common rock types like coal are distinct looking enough that they are usually easy to pick out as long as you’re aware that the rock type exists and have seen some examples (like the pictures above).

Sedimentary Rock FAQs

What Color are Sedimentary Rocks?

Sedimentary rocks can be almost any color, depending on the sediment source. While highly variable, clastic sedimentary rocks like sandstone are typically brown to reddish due to iron content. Organic and chemical sedimentary rocks are usually off-white due to large amounts of light-colored minerals like quartz and calcite.

Do Sedimentary Rocks Have Layers?

All sedimentary rocks have layers, which are often referred to as beds or strata. These layers may or may not be visible to the naked eye depending on the texture and color of the beds. The layers are most commonly parallel to one another, but can be curved or oblique in a sedimentary structure known as cross-bedding.

In some sedimentary rocks like mudstones or most chemical sedimentary rocks, seeing the layers is nearly impossible. The grain sizes and uniform colors make it extremely difficult to identify any bedding planes, even if they are technically present. Still, these rocks were deposited from the bottom up due to sediment accumulating over time, and therefore do have layers even if you can’t see them.

Similarly, in large-grained, poorly-sorted sedimentary rocks like breccia and conglomerate, it may be impossible to distinguish individual layers. This is because one layer may be many meters thick and because the larger cobbles and boulders disturb any visible bedding of the finer sediments.

Do Sedimentary Rocks Have Fossils?

Fossils can occur in almost any sedimentary rock, but are most commonly found in shales, mudstones, and limestones. The remains of living things settle with the sediment and are preserved within the rock, especially in low-energy environments like those required to create shales and mudstones.

Sedimentary rocks made up of larger grains are less likely to contain fossils because the faster-moving water required to transport their sediments is more likely to disturb the animal or plant remains. The fast-moving water also contains more oxygen which degrades and decomposes the remains before they can become fossilized.

Do Sedimentary Rocks React With Acid?

Sedimentary rocks containing calcium carbonate will react with a 10% hydrochloric acid solution. Limestone, which is almost entirely calcium carbonate, will react very strongly to acid. Any rock which with calcium carbonate cement will fizz with acid. Dolomite with fizz weakly on a freshly exposed surface, usually created by scratching it with a steel knife or nail.

Not all sedimentary rocks will react with acid, however. Many clastic rocks (sandstones and siltstones, for example) can have silica cement which won’t fizz with acid. Any rock fragments or minerals that aren’t calcium carbonate will give no reaction if exposed to hydrochloric acid, so while the presence of fizzing is a good indicator that a rock is sedimentary, the absence of fizzing does not necessarily mean that a rock isn’t sedimentary.

Do Sedimentary Rocks Have Gas Bubbles?

Sedimentary rocks do not have gas bubbles. Some sedimentary rocks have visible holes or pores that can be quite large, but they are not formed from gas bubbles. Large pores in rocks like limestone are called ‘vugs’ and are formed from the dissolution of minerals and weathering.

Only specific types of volcanic rocks like pumice, scoria, and basalt contain gas bubbles. Sedimentary rocks are formed from the compaction and cementation of sediment, leaving no room or opportunity for gas bubbles to become trapped in the rock.

Are Sedimentary Rocks Hard or Soft?

Sedimentary rocks with high silica content like sandstone and chert are very hard, with a Mohs hardness of around 7. Others that are comprised of softer minerals like gypsum, calcite, or halite are considered soft at 2 to 4 on the Mohs hardness scale.

It is common for geologists to refer to sedimentary rocks as ‘soft rocks’, while volcanic and metamorphic rocks are called ‘hard rocks’. These names are just a result of volcanic and metamorphic rocks generally being harder than most sedimentary rocks, but there are exceptions. If someone says they are a ‘soft rock’ geologist it means that they focus on sedimentary rocks, usually in the context of oil and gas exploration

This post is part of my rock identification series. If you want to keep reading about how to identify more rock types, this post should be next on your list.